Mamie Smith’s “Crazy Blues,” the first recording of an African-American singing the blues, revolutionized pop music. Witnesses claimed that after its release in 1920, the song could be heard coming from the open windows of virtually any black neighborhood in America. “That record turned around the recording industry,” remembered New Orleans jazzman Danny Barker. “There was a great appeal amongst black people and whites who loved this blues business to buy records and buy phonographs. Every family had a phonograph in their house, specifically behind Mamie Smith’s first record.”

Mamie Smith’s “Crazy Blues,” the first recording of an African-American singing the blues, revolutionized pop music. Witnesses claimed that after its release in 1920, the song could be heard coming from the open windows of virtually any black neighborhood in America. “That record turned around the recording industry,” remembered New Orleans jazzman Danny Barker. “There was a great appeal amongst black people and whites who loved this blues business to buy records and buy phonographs. Every family had a phonograph in their house, specifically behind Mamie Smith’s first record.”While blues music had been performed in the American South since the very beginning of the twentieth century, no one had made recordings of it before, largely due to racism and the assumption that African-Americans couldn’t – or wouldn’t – buy record players or 78s. “Crazy Blues” changed all that, sparking a mad scramble among record execs to record blues divas.

The stars they promoted in this short-lived era of “classic blues” were not the down-home country singers who’d record later in the Roaring Twenties, but the glittering, glamorous, and savvy veterans of tent shows, minstrel troupes, and the vaudeville stage. These mavericks defied stereotypes, and there wasn’t an Aunt Jemima among them (with the possible exception of Edith Wilson, who became the Aunt Jemima on the radio). Their lyrics were often erotic, frank, and cynical. Those who’d become most influential – Ma Rainey, Bessie Smith, and Ida Cox – had been performing blues for many years before their first recording sessions. Others emerged from black vaudeville and found quick fame and riches, only to be plunged back into obscurity and poverty. By the close of the 1920s, most of the classic blueswomen would see the popularity of their records eclipsed by male artists such as Blind Lemon Jefferson, Big Bill Broonzy, Lonnie Johnson, and Tampa Red.

Unlike country blues, the rural South’s party music, classic blues were conceived for the professional stage. Singers bedecked themselves in sumptuous gowns and paid careful attention to diction while belting out their woes to the accompaniment of a hot jazz ensemble or capable sideman. Whereas country singers could string together random verses as long as they wanted, most classic blueswomen relied on stately tunes by successful songwriters such as Clarence Williams, Porter Grainger, and the wily Perry Bradford, a key figure in the Mamie Smith story. A few of the best, though, wrote their own.

A veteran of vaudeville and the chorus line, the lovely Miss Smith was 37 years old when she made her historic recording o

f “Crazy Blues” in New York City. She had left Cincinnati’s tough Black Bottom neighborhood when she was ten years old to go on the road with The Four Dancing Mitchells. Five years later she joined the chorus of the Smart Set company, which landed her in Harlem. Mamie settled there and married her first husband, comedian Sam Gardner. Perry Bradford spotted her singing at a cabaret and gave her a spot in the musical Maid of Harlem at the Lincoln Theater. Her big number was his song “Harlem Blues.”

f “Crazy Blues” in New York City. She had left Cincinnati’s tough Black Bottom neighborhood when she was ten years old to go on the road with The Four Dancing Mitchells. Five years later she joined the chorus of the Smart Set company, which landed her in Harlem. Mamie settled there and married her first husband, comedian Sam Gardner. Perry Bradford spotted her singing at a cabaret and gave her a spot in the musical Maid of Harlem at the Lincoln Theater. Her big number was his song “Harlem Blues.”Bradford, who spent his afternoons working out new songs on the piano at Harlem’s Colored Vaudeville and Benevolent Association, had long dreamed of having African Americans record blues songs. According to his 1965 autobiography, Born with the Blues [Oak Publications], most New York musicians didn’t care for blues, which seemed to symbolize everything they tried to leave behind in the South. “Whenever I began drifting into the lowdown, melancholy strains of the levee-camp ‘jive,’ someone would yell to detract my attention,” Bradford remembered. “Anything to keep me from whipping out those distasteful blues.” A Southerner – Mississippi by way of Georgia – Bradford was certain blues could be alchemized into gold by creating a market in the South. For months he had been making the rounds of record companies, trying to sell them on his songs and his protégé, Mamie Smith. His persistence earned him the nickname “Mule.”

His first nibble came from Victor, one of the biggest labels in town. On January 10, 1920, Mamie Smith was ushered into a studio to cut a bare-bones trial recording of Bradford’s song “That Thing Called Love” set to her own piano accompaniment. Victor rejected it. The break Bradford had been searching for came soon afterward, when he caught the attention of Fred Hager, recording director for the fledgling OKeh label. “There are fourteen million Negroes in our great country,” Bradford told Hager, “and they will buy records if recorded by one of their own, because we are the only folks that can sing and interpret hot jazz songs just off the griddle correctly.” Asked what songs he had in mind, Bradford handed Hager sheet music for “That Thing Called Love” and “You Can’t Keep a Good Man Down.” Hager was impressed. He initially wanted Sophie Tucker, a white singer, to record the songs, but Bradford asked him to consider giving a black singer the chance. Mamie Smith, he promised, “will do more with those songs than a monkey can do with a peanut; she sings jazz songs with more soulful feeling than any other girls, for it’s natural for us.”

Hager’s decision was as brave as it was historic. In Born with the Blues, Bradford recounted: “Mr. Hager got a far-off look in his eyes and seemed somewhat worried, because of the many threatening letters he had received from some Northern and Southern pressure groups warning him not to have any truck with colored girls in the recording field. If he did, OKeh Products – phonograph machines and records – would be boycotted. May God bless Mr. Hager, for despite the many threats, it took a man with plenty of nerves and guts to buck those powerful groups and make the historical decision which would echo aroun’ the world. He pried open that old ‘prejudiced door’ for the first colored girl, Mamie Smith, so she could squeeze into the large horn – and shout with her strong contralto voice.”

The recording session was scheduled for Valentine’s Day, 1920. Hager had Mamie perform with his all-white studio band, credited on record as the Rega Orchestra. Mamie poured bluesy feeling into the pop tune “That Thing Called Love”:

“That thing called love has a sneaky feeling,

Being too sure of yourself sets your brain a-reeling,

You lay in bed but just can’t sleep,

Then you walk the streets and refuse to eat”

“Man,” Bradford enthused, “I was overjoyed when Mr. [Charles L.] Hibbard, the engineer, said, ‘It’s okay.’ . . . After Mamie finished recording ‘That Thing Called Love’ and ‘You Can’t Keep a Good Man Down’ that snowy morning in February 1920, I was itching to jump up and yell, right there in the studio, ‘Hallelujah, it’s done!’”

The Chicago Defender, the most widely read black newspaper, covered the event in its March 13, 1920, iss

ue: “Well, you’ve all heard the famous stars of the white race chirping their stuff on the different makes of phonograph records. Caruso has warbled his Jones to the delight of millions; Tettrazini has made ’em like it heavy and Nora Bayes has tickled their ears with a world of delight; but we have never – up to now – been able to hear one of our own ladies deliver the canned goods. Now we have the pleasure of being able to say that at last they have recognized the fact that we are here for their service; the OKeh Phonograph Company has initiated the idea by engaging the handsome, popular and capable vocalist, Mamie Gardner Smith of 40 W. 135 Street, New York City, and she has made her first record, ‘That Thing Called Love,’ a song by Perry Bradford, published by the Pace & Handy Music Co., and apparently destined to be one of that great company’s biggest hits. The OKeh records can be played on all phonographs and they do say that the one in question is a real dream.”

ue: “Well, you’ve all heard the famous stars of the white race chirping their stuff on the different makes of phonograph records. Caruso has warbled his Jones to the delight of millions; Tettrazini has made ’em like it heavy and Nora Bayes has tickled their ears with a world of delight; but we have never – up to now – been able to hear one of our own ladies deliver the canned goods. Now we have the pleasure of being able to say that at last they have recognized the fact that we are here for their service; the OKeh Phonograph Company has initiated the idea by engaging the handsome, popular and capable vocalist, Mamie Gardner Smith of 40 W. 135 Street, New York City, and she has made her first record, ‘That Thing Called Love,’ a song by Perry Bradford, published by the Pace & Handy Music Co., and apparently destined to be one of that great company’s biggest hits. The OKeh records can be played on all phonographs and they do say that the one in question is a real dream.”OKeh released “That Thing Called Love” in July. Bradford reported that they sold 10,000 copies “just as fast as the Button-Hole Factory at Scranton, Pennsylvania, could press and ship them all over the South.” In his autobiography Father of the Blues, W.C. Handy described, “In Chicago, large crowds of domestic servants and packinghouse workers waited outside Tate’s Music Store on South State Street to hear us demonstrate ‘That Thing Called Love’ and ‘You Can’t Keep a Good Man Down,’ as sung by Mamie. All over the country music stores sprung up like mushrooms and our folks were begging for OKeh agencies in vain. . . . We bought the records, shipped them and received a prompt check. This was followed by repeated orders of comparable size. Finally the Negro dealers got their agencies.”

Reports of strong sales down South – to whites and blacks – were no surprise to Bradford, who was certain Southerners would buy blues 78s: “They understand blues and jazz songs, for they’ve heard blind men on street corners in the South playing guitars and singing ’em for nickels and dimes ever since their childhood days.” In its July 31 issue, the Chicago Defender called on liberals to support the record’s release: “Lovers of music everywhere, and those who desire to help in any advance of the Race, should be sure to buy this record as encouragement to the manufacturers for their liberal policy and to encourage other manufacturers who may not believe that the Race will buy records sung by its own singers.”

A couple of weeks after the record’s release, Bradford stopped by Hager’s offic

e. “I’ve got news for you,” Hager told him. “Mamie’s record is selling very big in Philly and Chicago; the South, as you said, has gone head over heels for it, and down in Texas, Birmingham, and over in St. Louis, they are falling for the record just like leaves fall in Autumn-time.” Bradford informed Hager that Mamie had just been booked to perform an East Coast vaudeville tour and suggested that OKeh record her singing another song, “Harlem Blues,” before she left town. Hager told him to have Mamie and her musicians in the studio at 9:30 the following Monday morning.

e. “I’ve got news for you,” Hager told him. “Mamie’s record is selling very big in Philly and Chicago; the South, as you said, has gone head over heels for it, and down in Texas, Birmingham, and over in St. Louis, they are falling for the record just like leaves fall in Autumn-time.” Bradford informed Hager that Mamie had just been booked to perform an East Coast vaudeville tour and suggested that OKeh record her singing another song, “Harlem Blues,” before she left town. Hager told him to have Mamie and her musicians in the studio at 9:30 the following Monday morning.Bradford rushed off to assemble a band, which he named the Jazz Hounds, and to tell Mamie the good news. “At the time,” he wrote, “Mamie Smith had a five-room apartment on the top floor of Charlie Thorpe’s building at 888 West 135th Street, so I walked up to the top floor to her apartment and buzzed, ‘Mamie, we got a date set for you to record with our boys playing for you,’ and told her to come downtown to Bert Williams’ office tomorrow for a rehearsal. When Mom Smith heard the good news she jumped up and shouted, ‘The Lord Will Provide.’ Mamie’s husband Smitty started dancing all over the place.”

A few days later, on August 10, 1920, Mamie Smith and Her Jazz Hounds convened at the OKeh studio near Times Square. Bradford decided to change the title of “Harlem Blues” to “Crazy Blues.” While Bradford took credit for writing the song, James P. Johnson insisted its melody was derived from an old sporting-house ballad called “Baby, Get That Towel Wet.” Mamie’s lineup consisted of seasoned black musicians – Dope Andrews on trombone, Ernest Elliott on clarinet, Leroy Parker on violin, and Johnny Dunn on cornet. In their autobiographies, both Willie “The Lion” Smith and Perry Bradford claimed to have played the piano. The musicians fortified themselves with their favorite prohibition drink, blackberry juice and gin – Mamie didn’t join them – and then got to work. Bradford remembered that there were no written charts: “They were what I called ‘hum and head arrangements.’ I mean we would listen to the melody and the harmony of the piano and each man picked out his own harmony notes.”

A few days later, on August 10, 1920, Mamie Smith and Her Jazz Hounds convened at the OKeh studio near Times Square. Bradford decided to change the title of “Harlem Blues” to “Crazy Blues.” While Bradford took credit for writing the song, James P. Johnson insisted its melody was derived from an old sporting-house ballad called “Baby, Get That Towel Wet.” Mamie’s lineup consisted of seasoned black musicians – Dope Andrews on trombone, Ernest Elliott on clarinet, Leroy Parker on violin, and Johnny Dunn on cornet. In their autobiographies, both Willie “The Lion” Smith and Perry Bradford claimed to have played the piano. The musicians fortified themselves with their favorite prohibition drink, blackberry juice and gin – Mamie didn’t join them – and then got to work. Bradford remembered that there were no written charts: “They were what I called ‘hum and head arrangements.’ I mean we would listen to the melody and the harmony of the piano and each man picked out his own harmony notes.”“As we hit the introduction and Mamie started singing,” Bradford continued, “it gave me a lifetime thrill to hear Johnny Dunn’s cornet moaning those dreaming blues and Dope Andrews making some down-home slides on his trombone, while Ernest Elliott was echoing some clarinet jive along with Leroy Parker sawing his fiddle in the groove. Man, it was too much for me.” Her voice drenched with emotion, Mamie began with a theme that would echo through countless blues songs to come:

“I can’t sleep at night,

I can’t eat a bite,

’Cause the man I love,

He don’t treat me right”

Her performance built to a heartbreak climax:

“I went to the railroad

To lay my head on the track”

The musicians gave it everything they had, and Mamie sang in grand vaudeville style. After about twelve test takes, they finally produced a final take. “Tears of gladness came into my eyes after the first play-back and the feeling that grabbed me just wouldn’t go all during our eight-hour session – from 9:30 until 5:30,” Bradford wrote. “It was like a pleasant dream that came from heaven, because mental telepathy must have directed the band. We were playing just as we felt, with these home-made ‘hum and head’ arrangements, for I forgotten about leading the band and kept on playing the piano, as I’ve never played before – or any time since.” After recording the 78’s flip side, “It’s Right Here for You (If You Don’t Get It – ’Taint No Fault of Mine),” everyone called it a day. The musicians headed over to Mamie’s apartment, where her mother cooked a celebratory meal of black-eyed peas and rice.

And thus Mamie Smith earned her place in history as the first African American to record a blues song.

But is “Crazy Blues” a true blues? My best answer is that parts of it are and parts of it aren’t. The song’s ingenious structure mixes three verses of 12-bar blues with three verses of 16-bar professional songwriting that uses a harmonic idiom similar to what might appe

ar in a Scott Joplin rag or World War I pop song. The recording is in the key of E, and verses four and five are straight 12-bar blues. Verse two is a slightly modified 12-bar blues, going to the dominant in its second bar. Verses one, three, and six are 16-bar structures with trickier chord progressions and some chromaticisms, such as the descending bass line in the ninth through eleventh bars of verse one. Verses three and six feature secondary dominants that sound relatively “sophisticated” next to simpler blues verses two, four, and five. Listen to it here and judge for yourself: www.archive.org/details/MamieSmithHerJazzHounds.

ar in a Scott Joplin rag or World War I pop song. The recording is in the key of E, and verses four and five are straight 12-bar blues. Verse two is a slightly modified 12-bar blues, going to the dominant in its second bar. Verses one, three, and six are 16-bar structures with trickier chord progressions and some chromaticisms, such as the descending bass line in the ninth through eleventh bars of verse one. Verses three and six feature secondary dominants that sound relatively “sophisticated” next to simpler blues verses two, four, and five. Listen to it here and judge for yourself: www.archive.org/details/MamieSmithHerJazzHounds.Issued as OKeh 4169, “Crazy Blues” was credited to “Mamie Smith and Her Jazz Hounds” and described as a “Popular Blue Song.” Sales of the 78 skyrocketed beyond anyone’s wildest expectations. In Harlem alone, 75,000 copies were reportedly sold in less than a month. “Pullman porters bought them by the dozens at a dollar per copy,” remembered Bradford, “and sold them in rural districts for two dollars.”

Mamie and her band were back in the studio on September 12, 1920, for a follow-up 78, “Fare Thee Honey

Blues” backed with “The Road is Rocky (But I Am Gonna Find My Way).” In his autobiography, Bradford writes that this was his final recording date for the OKeh label: “On this last session Mr. Everhart, a big dealer from Norfolk, Virginia, was in the studio and booked Mamie Smith and the Jazz Hounds for a one-night performance at a salary of $2,000. Then he, Mamie and the Hounds, sold over ten thousand records, because he had ten helpers handing out the records (at one dollar per copy) so fast during that half-hour intermission under Billy Sunday’s big Gospel Tent that it looked like Barnum & Bailey giving away silver dollars.” Mamie and her band – sans Bradford – soon cut two more 78s, “Mem’ries of You Mammy” b/w “If You Don’t Want Me Blues” and “Don’t Care Blues” b/w “Lovin’ Sam from Alabam.”

Blues” backed with “The Road is Rocky (But I Am Gonna Find My Way).” In his autobiography, Bradford writes that this was his final recording date for the OKeh label: “On this last session Mr. Everhart, a big dealer from Norfolk, Virginia, was in the studio and booked Mamie Smith and the Jazz Hounds for a one-night performance at a salary of $2,000. Then he, Mamie and the Hounds, sold over ten thousand records, because he had ten helpers handing out the records (at one dollar per copy) so fast during that half-hour intermission under Billy Sunday’s big Gospel Tent that it looked like Barnum & Bailey giving away silver dollars.” Mamie and her band – sans Bradford – soon cut two more 78s, “Mem’ries of You Mammy” b/w “If You Don’t Want Me Blues” and “Don’t Care Blues” b/w “Lovin’ Sam from Alabam.”With all this Mamie Smith mania, New York City suddenly became the blues recording capital of the world. Singers and orchestra leaders, publishers, talent scouts, record execs – a

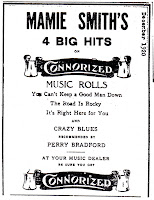

ll were ready to cash in. “Everybody tried to sing the blues,” explained Thomas A. Dorsey, “because the blues was paying off.” Variety noted that Mamie Smith’s records had “caught on with the Caucasians” and that “Perry Bradford and the Clarence Williams Music Co. are among the representative Negro music men cleaning up from mechanical royalties with the sheet music angle negligible and almost incidental. . . . Colored singing and playing artists are riding to fame and fortune with the current popular demand for ‘blues’ disk recordings and because of the recognized fact that only a Negro can do justice to the native indigo ditties such artists are in demand.” By December 1920, Mamie Smith music rolls were being advertised; for people with player pianos, these rolls were the equivalent of modern karaoke backing tracks.

ll were ready to cash in. “Everybody tried to sing the blues,” explained Thomas A. Dorsey, “because the blues was paying off.” Variety noted that Mamie Smith’s records had “caught on with the Caucasians” and that “Perry Bradford and the Clarence Williams Music Co. are among the representative Negro music men cleaning up from mechanical royalties with the sheet music angle negligible and almost incidental. . . . Colored singing and playing artists are riding to fame and fortune with the current popular demand for ‘blues’ disk recordings and because of the recognized fact that only a Negro can do justice to the native indigo ditties such artists are in demand.” By December 1920, Mamie Smith music rolls were being advertised; for people with player pianos, these rolls were the equivalent of modern karaoke backing tracks.

The singer became an immediate concert draw. Mamie Smith and Her Jazz Hounds initially earned $400 to $500 net per weeklong appearance, but her fees would soon rise. Bradford recalled that Porter

Grainger always played piano at Mamie’s appearances.

Grainger always played piano at Mamie’s appearances.On November 29, 1920, the Putnam Theatre in Brooklyn ran a newspaper ad for Mamie Smith and Her Jazz Hounds, proclaiming her an “Attraction Extraordinary.” Smaller print declared that Mamie “just finished a record breaking engagement at the Lafayette Theatre, N.Y., and the Dunbar Theatre, Philadelphia, Pa. Do not fail to hear this sensational singer, who has been made famous by her new phonograph records.” Onstage, Mamie tried to duplicate her records, explaining to the Washington Post on December 19, 1920: “Thousand of people who come to hear me . . . expect much, and I do not intend that they shall be disappointed. They have heard my phonograph records and they want me to sing these songs that same as I do in my studio in New York. Another thing I believe my audiences want to see me becomingly gowned, and I have spared no expense or pains . . . for I feel that the best is none too good for the public that pays to hear a singer.”

Lucille Hegamin was the first Mamie Smith competitor ushered into a studio, cutting an unissued Victor test of “Dallas Blues” on October 11, 1920, with Fletcher Henderson on piano. In November, backed by Harris’ Blues and Jazz Seven, she cut her first hit, “The Jazz Me Blues,

” which eventually came out on more than a dozen labels. By 1921, blues recording sessions were going full-swing. Mary Stafford, advertised as the “First Colored Girl to Sing for Columbia,” launched her recording career in early January 1921. In February, Lucille Hegamin had a hit with “Arkansas Blues.” In March, Cardinal Records recorded Ethel “Sweet Mama Stringbean” Waters’ first record, and Emerson Phonograph proclaimed Lillyn Brown “not only a favorite with her own people, but with white audiences as well.” In April, Gertrude Saunders became Mamie Smith’s labelmate at OKeh. Stage star Edith Wilson began recording for Columbia in September. Lavinia Turner cut for Perfect and Pathe Actuelle, Esther Bigeau made 78s for OKeh, and Lulu Whidby, Alberta Hunter, and Katie Crippen records came out on Black Swan.

” which eventually came out on more than a dozen labels. By 1921, blues recording sessions were going full-swing. Mary Stafford, advertised as the “First Colored Girl to Sing for Columbia,” launched her recording career in early January 1921. In February, Lucille Hegamin had a hit with “Arkansas Blues.” In March, Cardinal Records recorded Ethel “Sweet Mama Stringbean” Waters’ first record, and Emerson Phonograph proclaimed Lillyn Brown “not only a favorite with her own people, but with white audiences as well.” In April, Gertrude Saunders became Mamie Smith’s labelmate at OKeh. Stage star Edith Wilson began recording for Columbia in September. Lavinia Turner cut for Perfect and Pathe Actuelle, Esther Bigeau made 78s for OKeh, and Lulu Whidby, Alberta Hunter, and Katie Crippen records came out on Black Swan.Among the first wave of classic blueswomen who recorded in 1921, only Alberta Hunter, Ethel Waters, and Edith Wilson would have enduring success. Mary Stafford cut a half-dozen 78s by the year’s end and made a single side for Perfect in ’26 before vanishing from the scene. Lavinia Turner’s days in front of the horn were over by October ’22, with six 78s to her credit. Lillyn Brown cut only two; Lulu Whidby made variations of only one. Gertrude Saunders had a career total of three 78s. Katie Crippen’s four titles with Fletcher Henderson’s Novelty Orchestra helped her land a vaudeville tour, but she was soon working outside of musi

c.

c.In truth, no one could touch Mamie Smith in 1921. The February 15, 1921, issue of the trade journal The Talking Machine World conveyed some of the national fervor for the singer in an article titled “Has Designs on the Preacher”: “The advertising department of the General Phonograph Corp., New York, received recently an interesting letter from a Mamie Smith enthusiast in North Carolina. Evidently this admirer of the Mamie Smith records has studied jazz music more carefully than the English language, but the letter itself is an indication of the popularity that Mamie Smith OKeh records have attained in all sections of the country. In fact, this letter is only one of many of similar tenor that the General Phonograph Corp. has received during the past few months. It reads:

“‘I rite you to please send me one of your latest catalog of latest popular songs and musical comedy hits popular dacing numbers I got the Crazy Blues all ready and if you have any other latest Blues sung by Mamie Smith and her jazz hounds send along 2 or 3 C.O.D. with the catalog. I want something that will almost make a preacher come down out of the pulpit and go to dancing and hang his head and cry I want all you send to be Blues.’

“The Mamie Smith OKeh library is being steadily augmented by new records made by this popular artist, and the phenomenal success of these records is reflected in the enthusiastic reports of OKeh jobbers and dealers throughout the country who state that the demand for Mamie Smith recordings has far exceeded all expectations.”

Mamie Smith cut twenty-two songs in 1921, including “Jazzbo Ball,” “‘U’ Need Some Loving Blues,” “Mamma Whip! Mamma Spank! (If Her Daddy Don’t Come Home),” and the jazzy “A Little Kind Treatment (Is Exactly What I Need)” (http://www.archive.org/details/JosephSamuelsJazzBandVmamieSmith-ALittleKindTreatment1921atment1921 ). Between sessions, she kept a grueling schedule of concert appearances. The March 15, 1921, issue of The Talking Machine World covere

d her appearances in Chicago: “Mamie Smith and her jazz hounds came, saw, and conquered in Chicago during the month of February. She played to large audiences on the South Side at the Avenue Theatre with immense success. The Chicago Defender, a newspaper circulating among the colored people of the city, carried large advertisement featuring the OKeh stock, ‘Hear this world-famous phonograph star,’ read the advertisement, ‘sing ‘Crazy Blues’ and all her latest hits, and then hear her popular OKeh records, the greatest blues records of the century. Mamie Smith records have enjoyed tremendous sale in all parts of the country.’”

d her appearances in Chicago: “Mamie Smith and her jazz hounds came, saw, and conquered in Chicago during the month of February. She played to large audiences on the South Side at the Avenue Theatre with immense success. The Chicago Defender, a newspaper circulating among the colored people of the city, carried large advertisement featuring the OKeh stock, ‘Hear this world-famous phonograph star,’ read the advertisement, ‘sing ‘Crazy Blues’ and all her latest hits, and then hear her popular OKeh records, the greatest blues records of the century. Mamie Smith records have enjoyed tremendous sale in all parts of the country.’”A month later, in a full-page ad in The Talking Machine World, OKeh Records reported that “Mamie Smith, assisted by her All Star Revue, a large company of well trained artists, is giving concerts in all the large cities throughout the country. Due to her popularity, capacity-filled houses are guaranteed. And the enthusiasm created, in turn, has in every instance stimulated the sale of her records. She has recently filled engagements in Chicago, Indianapolis, Evansville, Lexington, Memphis, Little Rock, Tulsa, Oklahoma City, Dallas, Fort Worth, Houston, Waco, Beaumont, New Orleans, St. Louis, Chattanooga, Atlanta, Savannah, Richmond, Norfolk, Wilmington, Philadelphia, and numerous other cities.”

Meanwhile back in New York City, Perry Bradford was beset with problems. Not long after the Pace-Handy Co. publ

ished “Crazy Blues,” he was sued for having previously sold the same song to Frederick V. Bowers, Inc., under the title “The Broken Hearted Blues,” and to the Q.R.S. company as “Wicked Blues.” Bradford settled out of court. He had legal problems with Mamie Smith as well. His book recounts that in May 1921 Mamie’s “new boyfriend,” Ocie Wilson, gave Bradford a “mouth-full of his large fists” when he showed up at their door with a process server. Bradford sued them for assault and battery, and lost in court. “From then on,” he wrote, “I didn’t bother Mamie anymore.” Covering another copyright case, The New York Clipper reported in January 1923 that Bradford had instigated others to perjure themselves on his behalf, and that the songwriter had served four months in the Essex County Penitentiary.

ished “Crazy Blues,” he was sued for having previously sold the same song to Frederick V. Bowers, Inc., under the title “The Broken Hearted Blues,” and to the Q.R.S. company as “Wicked Blues.” Bradford settled out of court. He had legal problems with Mamie Smith as well. His book recounts that in May 1921 Mamie’s “new boyfriend,” Ocie Wilson, gave Bradford a “mouth-full of his large fists” when he showed up at their door with a process server. Bradford sued them for assault and battery, and lost in court. “From then on,” he wrote, “I didn’t bother Mamie anymore.” Covering another copyright case, The New York Clipper reported in January 1923 that Bradford had instigated others to perjure themselves on his behalf, and that the songwriter had served four months in the Essex County Penitentiary.Mamie Smith continued to fare much better than her former partner. An ad for “Sax-

o-Phony Blues” in the October 15, 1921, issue of The Talking Machine World stated that “September 24th marked the opening date of Mamie Smith’s concert tour for the coming season. Her personal appearances in all the large towns will be a tremendous boom to her records. Her first engagement will be in the New England territory. She will tour as far South as Florida. Sax-O-Phoney Blues looks like the feature hit in her song review. This means big business for every OKeh jobber who has sufficient stock on hand to meet ready requests. Mamie Smith is working Sax-O-Phoney Blues hard.”

o-Phony Blues” in the October 15, 1921, issue of The Talking Machine World stated that “September 24th marked the opening date of Mamie Smith’s concert tour for the coming season. Her personal appearances in all the large towns will be a tremendous boom to her records. Her first engagement will be in the New England territory. She will tour as far South as Florida. Sax-O-Phoney Blues looks like the feature hit in her song review. This means big business for every OKeh jobber who has sufficient stock on hand to meet ready requests. Mamie Smith is working Sax-O-Phoney Blues hard.”In Mamie Smith’s prime, her stage appearances netted her up to $1,500 a week. Bedecked in diamonds, plumes, and a shimmering gown, she could get a standing ovation just by strutting across the stage. Bubber Miley, Coleman Hawkins, and many other promising young players passed through her band. She released nine more vaudeville-style blues and pop 78s in 1922, including “Wabash Blues,” “Mamie Smith Blues,” and “Mean Daddy Blues,” featuring Coleman Hawkins on tenor sax. By 1923, though, her record sales were being eclipsed by those of other singers, notably Bessie Smith, Alberta Hunter, Clara Smith, Ida Cox, and, by year’s end, the South’s favorite blues singer, the great Ma Rainey. After recording four 78s in July and August 1923, Mamie Smith was dropped from the OKeh label. She made three 78s for the small Ajax label in 1924, and two more for Victor in 1926. Mamie Smith’s glory days were over. All totaled, she earned an estimated career royalty of $100,000.

For a while, Mamie continued to be a draw in theaters. Thomas C. Fleming, a writer for the Sun-Reporter, San Francisco’s African-American

weekly, described seeing her onstage for http://www.sfmuseum.org/ : “In 1924, a musical revue that starred Mamie Smith, the great blues singer, had a long run in San Francisco. After closing, it toured some cities in the Sacramento Valley, including Chico, where it appeared at the Majestic for two nights. I attended both nights, fascinated with a show of that size playing in the hick towns. Chico had a tiny black population, so most of the audience was white. The cast, which was all black, included Smith, an orchestra of about eight pieces – saxophone, clarinet, piano, drums, trumpet, trombone, banjo -- a chorus line of maybe six girls, all good-looking, and a number of comedians. One I recall with pleasure was Frisco Nick, who staged a hilarious dance while he sang ‘Three O’Clock in the Morning,’ a great waltz hit, with a broom as his partner. Except for Smith, the entire cast was from the San Francisco Bay Area. Mamie Smith was about on a level with Bessie Smith. She played the black circuit theaters in the Middle West and the East Coast. The black circuit didn’t exist on the West Coast, because they didn’t have separate theaters for blacks and whites, although in some places, such as Portland, Oregon, blacks coul

weekly, described seeing her onstage for http://www.sfmuseum.org/ : “In 1924, a musical revue that starred Mamie Smith, the great blues singer, had a long run in San Francisco. After closing, it toured some cities in the Sacramento Valley, including Chico, where it appeared at the Majestic for two nights. I attended both nights, fascinated with a show of that size playing in the hick towns. Chico had a tiny black population, so most of the audience was white. The cast, which was all black, included Smith, an orchestra of about eight pieces – saxophone, clarinet, piano, drums, trumpet, trombone, banjo -- a chorus line of maybe six girls, all good-looking, and a number of comedians. One I recall with pleasure was Frisco Nick, who staged a hilarious dance while he sang ‘Three O’Clock in the Morning,’ a great waltz hit, with a broom as his partner. Except for Smith, the entire cast was from the San Francisco Bay Area. Mamie Smith was about on a level with Bessie Smith. She played the black circuit theaters in the Middle West and the East Coast. The black circuit didn’t exist on the West Coast, because they didn’t have separate theaters for blacks and whites, although in some places, such as Portland, Oregon, blacks coul d sit only in the balcony.”

d sit only in the balcony.”Mamie was still drawing crowds four years later, when in January 1928 the Lincoln Theatre in Harlem ran an ad for “Harlem’s Own Record Star, Mamie Smith and Her Gang,” with the subtitle “You’ve Seen the Rest, Now See the Best. ’Nuf Sed.” That September, Mamie opened at the Lafayette Theatre in the musical comedy Sugar Cane.

In March 1929 OKeh Records recalled Miss Smith to the studio. She was in grand form belting out pistol-ho

t, risqué blues, but OKeh shelved all five recordings. In its March 23, 1929, issue, the Chicago Defender carried a two-line note reporting “Mamie Smith will soon make her debut in talking pictures in The Blues Singer.” No film of this title was released, but later that year Columbia released Jail House Blues, a silent film short with accompanying musical discs. Oddly dressed in a huge Tam-o-shanter, plaid skirt, and tight sweater with a feather boa collar, Mamie can be seen singing “Jail House Blues” on www.youtube.com/watch?v=jb4tyPjxHdE .

t, risqué blues, but OKeh shelved all five recordings. In its March 23, 1929, issue, the Chicago Defender carried a two-line note reporting “Mamie Smith will soon make her debut in talking pictures in The Blues Singer.” No film of this title was released, but later that year Columbia released Jail House Blues, a silent film short with accompanying musical discs. Oddly dressed in a huge Tam-o-shanter, plaid skirt, and tight sweater with a feather boa collar, Mamie can be seen singing “Jail House Blues” on www.youtube.com/watch?v=jb4tyPjxHdE .Mamie Smith’s recording career ended a decade after it began with four OKeh tracks in February 1931. All of these were songs were released, with “Jenny’s Ball” becoming the most popular. Miss Smith reportedly retired from music after their release. I’ve been unable to find any account of her goings-on during the 1930s.

Eight years later, Mamie Smith attempted a comeback – in films. She sang an expressive, slowed-down version of “Harlem Blues” with Lucky Millinder and His Orchestra in the 1939 black gangster musical Paradise in Harlem (www.youtube.com/watch?v=8AN3pxrRzMM&feature=related). Her co-stars included Edna Mae Harris and the Juanita Hall Singers. The film’s press book called it “The ‘Gone with the Wind’ of Colored Pictures,’” with “The Greatest Colored Cast Ever Assembled in One Picture.” In addition to singing, Mamie had a featured role playing – who else? – Miss Mamie.

The following year Miss Smith played a small part in the Aetna Film’s all-black Mystery in Swing. She appeared in two films in 1941, both produced for International Roadshows Release by Jack Goldberg, who’d staged road shows for Mamie in the 1920s and was reportedly her husband when these films were made. Sunday Sinners was described in its press book as “A Dramatic Thunderbolt – A Conflict of Riff Raff and Righteousn

ess,” and Mamie received top billing over Edna Mae Harris, Alec Lovejoy, Norman Astwood, and “A Brown Skin Chorus of Beauties.” Her other film, Murder on Lenox Avenue, was touted as “A Modern Story of Harlem Life” with “Donald Heywood’s Most Singable and Danceable Score.” Astwood, Lovejoy, and Harris rejoined Miss Smith in the cast. (Murder on Lenox Avenue can be legally downloaded at www.archive.org/details/murder_on_lenox_ave1941 .) Her final celluloid role was in the 1942 soundie “Because I Love You” with Lucky Millinder. From here, Mamie Smith’s trail disappears.

ess,” and Mamie received top billing over Edna Mae Harris, Alec Lovejoy, Norman Astwood, and “A Brown Skin Chorus of Beauties.” Her other film, Murder on Lenox Avenue, was touted as “A Modern Story of Harlem Life” with “Donald Heywood’s Most Singable and Danceable Score.” Astwood, Lovejoy, and Harris rejoined Miss Smith in the cast. (Murder on Lenox Avenue can be legally downloaded at www.archive.org/details/murder_on_lenox_ave1941 .) Her final celluloid role was in the 1942 soundie “Because I Love You” with Lucky Millinder. From here, Mamie Smith’s trail disappears.She reportedly died penniless on August 16, 1946, and was buried in an unmarked community grave. Seventeen years later, musicians in Iserlohn, West Germany, organized a hot jazz benefit to buy her a tombstone inscribed “Mamie Smith 1983-1946 First Lady of the Blue s.” They shipped the stone to New York, where Victoria Spivey, herself a classic blueswoman, and Len Kunstadt, publisher of Record Research magazine, arranged to have Mamie Smith re-interred in the Frederick Douglass Memorial Park in Richmond, New York. They celebrated the event with January 27, 1964, gala honoring Mamie at New York’s Celebrity Club. Among the attendees were several of Mamie’s peers from the early 1920s, including Lucille Hegamin, Alberta Hunter, Gertrude Saunders, Lillyn Brown, Rosa Henderson, and organizer Victoria Spivey. In 1994, “Crazy Blues” by Mamie Smith and Her Jazz Hounds was honored with the Grammy Hall of Fame Award.

s.” They shipped the stone to New York, where Victoria Spivey, herself a classic blueswoman, and Len Kunstadt, publisher of Record Research magazine, arranged to have Mamie Smith re-interred in the Frederick Douglass Memorial Park in Richmond, New York. They celebrated the event with January 27, 1964, gala honoring Mamie at New York’s Celebrity Club. Among the attendees were several of Mamie’s peers from the early 1920s, including Lucille Hegamin, Alberta Hunter, Gertrude Saunders, Lillyn Brown, Rosa Henderson, and organizer Victoria Spivey. In 1994, “Crazy Blues” by Mamie Smith and Her Jazz Hounds was honored with the Grammy Hall of Fame Award.

###

Help support this blog and independent music journalism by making a small donation via the Paypal button at the bottom of this page.

###

Thanks to Bill Ferris and the University of Mississippi’s Blues Archive and to Tim Gracyk for their assistance with research and graphics. Tim’s website, www.gracyk.com, is an excellent source for learning the basics of buying and selling 78s.

s.” They shipped the stone to New York, where Victoria Spivey, herself a classic blueswoman, and Len Kunstadt, publisher of Record Research magazine, arranged to have Mamie Smith re-interred in the Frederick Douglass Memorial Park in Richmond, New York. They celebrated the event with January 27, 1964, gala honoring Mamie at New York’s Celebrity Club. Among the attendees were several of Mamie’s peers from the early 1920s, including Lucille Hegamin, Alberta Hunter, Gertrude Saunders, Lillyn Brown, Rosa Henderson, and organizer Victoria Spivey. In 1994, “Crazy Blues” by Mamie Smith and Her Jazz Hounds was honored with the Grammy Hall of Fame Award.

s.” They shipped the stone to New York, where Victoria Spivey, herself a classic blueswoman, and Len Kunstadt, publisher of Record Research magazine, arranged to have Mamie Smith re-interred in the Frederick Douglass Memorial Park in Richmond, New York. They celebrated the event with January 27, 1964, gala honoring Mamie at New York’s Celebrity Club. Among the attendees were several of Mamie’s peers from the early 1920s, including Lucille Hegamin, Alberta Hunter, Gertrude Saunders, Lillyn Brown, Rosa Henderson, and organizer Victoria Spivey. In 1994, “Crazy Blues” by Mamie Smith and Her Jazz Hounds was honored with the Grammy Hall of Fame Award.###

Help support this blog and independent music journalism by making a small donation via the Paypal button at the bottom of this page.

###

Thanks to Bill Ferris and the University of Mississippi’s Blues Archive and to Tim Gracyk for their assistance with research and graphics. Tim’s website, www.gracyk.com, is an excellent source for learning the basics of buying and selling 78s.

No comments:

Post a Comment