In the decade following World War II, the epicenters of the urban blues boom were in Chicago, Houston, Oakland, and Los Angeles. But other cities made essential contributions as well, notably Detroit, where musicians from the Black Bottom to Paradise Valley specialized in swing, jump blues, boogie-woogie piano, and electrified country blues. Detroit’s most happening scene was along Hastings Street, with its black-owned shops, clubs, and restaurants, as well as its gambling dens, bordellos, and ongoing house parties. John Lee Hooker, Eddie Burns, Baby Boy Warren, Willie D. Warren, Calvin Frazier, Henry Smith, Washboard Willie, Eddie Kirkland, Bobo Jenkins, and other Detroit bluesmen came here to play for tips and cut storefront singles for local blues entrepreneurs such as Bernie Bessman and Joe Von Battle. Eddie Burns, 82, is the last of Detroit’s early postwar legends to still live in the Motor City.

Born in Belzoni, Mississippi, Burns is the eldest brother of Chicago bluesman Jimmy Burns. Raised around Clarksdale, Mississippi, he was inspired by Sonny Boy Williamson I records and in-person encounters with Sonny Boy Williamson II to learn harmonica during his teens. In 1947 Burns left Mississippi for good, taking a job as a troubleshooter for the Illinois Central railway company. In Iowa, he formed a guitar-harmonica duo with John T. Smith, who accompanied him to Detroit in 1948. Soon after his arrival, Burns met another bluesman who’d been raised around Clarksdale, John Lee Hooker, whose “Boogie Chillen” was just about to be released. “Oh, Eddie and I became good buddies right away,” Hooker told me. “We was so close, and he listened to me to get a lot of his stuff. When I first met him, he was only playin’ harmonica, which he still know how to play now. And oooh, he was so good!”

John Lee Hooker invited Burns to blow harp at his next session, which produced the Sensation singles “Burnin’ Hell” and “Miss Eloise,” as well as “Sailing Blues,” “Black Cat Blues,” and “I Had a Dream,” which all later came out on albums. That same day, Burns and Smith

also recorded on their own, with “Notoriety Woman” b/w “Papa’s Boogie” coming out on Palda credited to the Swing Brothers. Hooker soon found work at the Harlem Inn and had Burns sub for him when a doctored drink laid him low. Burns, by now teaching himself guitar, put together his first group at the Harlem Inn.

also recorded on their own, with “Notoriety Woman” b/w “Papa’s Boogie” coming out on Palda credited to the Swing Brothers. Hooker soon found work at the Harlem Inn and had Burns sub for him when a doctored drink laid him low. Burns, by now teaching himself guitar, put together his first group at the Harlem Inn.During the 1950s John Lee Hooker became blues star, releasing dozens of singles on various labels. Burns fared less well financially, working day jobs, playing small clubs, and participating in a scattering of local sessions. In 1951, Hooker and John T. Smith supported him on a series of originals recorded by Joe Von Battle, who sold the titles to Gotham. Despite Burns’ appealingly raw vocals and Sonny Boy I-inspired harp, these performances of “Making a Fool Out of Me,” “Where Were You Last Night Baby,” and “Squeeze Me Baby” remained unissued for many years. Von Battle was more successful with 1952’s “Hello Miss Jessie Lee” and “Dealing with the Devil,” leasing the sides to Deluxe. The single’s success brought Burns a steady, better-paying gig at the Tavern Lounge, which he celebrated in 1953’s “Tavern Lounge Boogie,” on Modern. By then he’d expanded his band to piano, two guitars, and drums, while the sounds of his own harp and guitar remained lean and countrified.

Burns married his first wife in 1953 and soon started having children. He worked at a Dodge automobile factory and played four or five nights a week to all-black audiences. In 1954 he cut the Hastings Stre

et classics “Superstition”/“Biscuit Baking Mama,” released by Checker credited to Big Ed and His Combo. Eddie played guitar on his final single of the decade, 1957’s “Treat Me Like I Treat You”/“Don’t Cha Leave Me Baby,” released on JVB and Chess. By then his blues were going out of fashion, and he began playing guitar at club dates and sessions with younger harmonica player Little Sonny Willis.

et classics “Superstition”/“Biscuit Baking Mama,” released by Checker credited to Big Ed and His Combo. Eddie played guitar on his final single of the decade, 1957’s “Treat Me Like I Treat You”/“Don’t Cha Leave Me Baby,” released on JVB and Chess. By then his blues were going out of fashion, and he began playing guitar at club dates and sessions with younger harmonica player Little Sonny Willis.Signing with Harvey Fuqua’s Harvey label, Burns scored a regional hit with 1961’s exhilarating “Orange Driver” and “Hard Hearted Woman,” both with Marvin Gaye on drums. His second and final single for the label, “(Don’t Be) Messin’ with My Bread,” inspired a cover by John Lee Hooker. For the next coupl

e of years Burns mostly worked as a sideman and cut two singles for the Von label in 1965. The following summer he reunited with John Lee Hooker at Chess Records’ Chicago studio. “I recorded with Eddie Burns again, for Chess, because we was buddies, and he was playin’ so good at the time,” Hooker explained. The resulting album, The Real Folk Blues

e of years Burns mostly worked as a sideman and cut two singles for the Von label in 1965. The following summer he reunited with John Lee Hooker at Chess Records’ Chicago studio. “I recorded with Eddie Burns again, for Chess, because we was buddies, and he was playin’ so good at the time,” Hooker explained. The resulting album, The Real Folk BluesClick on the blue links to download songs and albums.

By the late 1960s, most of the establishments along Hastings Street had closed or been torn down to make way for a freeway. Nearly all of the small, independent blues labels had folded or been sold, and Motown, R&B, and rock and roll had become Detroit’s prominent sound. Outside of a few supper clubs and bars in Detroit and Ann Arbor, few blues venues were available to pure blues musicians

, and by the early 1970s Bobo Jenkins, Baby Boy Warren, Dr. Ross, and many other musicians were working in automotive plants. With six children and a second wife, Burns, who’d worked at Dodge, attended Detroit’s Wolverine trade school and learned welding. “I didn’t know no skilled labor job,” he says, “and I did that because my hands was important. You gotta be careful with your hands if you play guitar.”

, and by the early 1970s Bobo Jenkins, Baby Boy Warren, Dr. Ross, and many other musicians were working in automotive plants. With six children and a second wife, Burns, who’d worked at Dodge, attended Detroit’s Wolverine trade school and learned welding. “I didn’t know no skilled labor job,” he says, “and I did that because my hands was important. You gotta be careful with your hands if you play guitar.” Finding few bookings as a modern bluesman or Top-10 soul performer, Burns expanded his style on acoustic guitar, learning the down-home country blues of Tommy McClennan. His return-to-roots paid off in 1972, when he toured England and recorded his first albums, the all-original Detroit Black Bottom for Big Bear Blues and Bottle Up & Go, with its Tom

my McClennan covers, for Action Records. Burns returned to Europe as part of “The American Blues Legends 1975” tour with Billy Boy Arnold, Jimmy Lee Robinson, and Homesick James. He won critical praise for opening his shows alone on harmonica and guitar, and then burning hard with a band that included Robinson on bass. Back home, he played the festival circuit and recorded Detroit Reunion with Eddie Kirkland. In 1980, he had a brief, unsuccessful flirtation with running his own label. The European-based Moonshine label then issued Treat Me Like I Treat You, a compilation of Bur

my McClennan covers, for Action Records. Burns returned to Europe as part of “The American Blues Legends 1975” tour with Billy Boy Arnold, Jimmy Lee Robinson, and Homesick James. He won critical praise for opening his shows alone on harmonica and guitar, and then burning hard with a band that included Robinson on bass. Back home, he played the festival circuit and recorded Detroit Reunion with Eddie Kirkland. In 1980, he had a brief, unsuccessful flirtation with running his own label. The European-based Moonshine label then issued Treat Me Like I Treat You, a compilation of Bur ns’ early singles and a pair of 1982 performances.

ns’ early singles and a pair of 1982 performances.Burns recorded his first CD, Detroit

At the time of our interview, Burns was living on Detroit’s East Side with his wife of 30 years. He was still writing songs, playing festivals, and gigging around the town where he made his name. On a frozen afternoon in November 2000, we met at the comfortable, immaculately kept home he’s owned since 1970. Surrounded by photographs of his family, he spoke of his life in music, his desire to record another album, and his spiritual beliefs. He also lived up to the praise that John Lee Hooker and others have bestowed upon him: Eddie Burns is, indeed, one of the nicest musicians you could meet.

This interview originally appeared as the cover story of Living Blues magazine, issue #156, in March/April 2001.

****

Your brother Jimmy Burns plays some fine blues.

He’s a good guy. Leaving Here Walking is his first blues LP, because, see, he was a rhythm and blues artist before he was a blues artist. So now he’s carryin’ both along together, and they workin’ pretty good for him. I guess it was in his blood, because our father, Albert, was a musician. He died in a head-on collision in Clarksdale, Mississippi, in 1962.

How much older are you than Jimmy?

Oh, Jimmy’s the baby, so I would say about 15 or 16 years. He didn’t remember me when I left; he was too young. I got two other brothers, and he’s the last one of nine kids. We had a brother that passed at the age of 13.

You were born in Belzoni, Mississippi?

Yeah, but I don’t know anything about it because I didn’t grow up there. I grew up around Clarksdale, Webb, and Dublin.

Did you live on a farm?

Ah, somewhat. See, I was raised by my grandparents – my mother’s father and mother. And my granddad, he was a gambler, juke joint man, that kind of thing, and then he worked for the white folks. She did too. She cooked. And so I did very little farming myself, and never did like it. Still don’t. I admire it because it’s important.

Left: Tommy McClennan

Left: Tommy McClennan Did your grandparents have a collection of 78s?

We had a record player and lights in our house. We had a Philco radio that played 78s – ten of them – back around 1938, ’39. And all of the people that was out there back then was playin’ blues. I liked John Lee Williamson, which was Sonny Boy I, Jazz Gillum, Big Bill Broonzy, Memphis Slim, Lil Green, Walter Davis. Tommy McClennan was my favorite, because I idolized him. Still do – I still like him. He was so soulful, if you listen to his old stuff. That was my first real influence, other than John Lee Williamson. Them two was like running along together with me. Tommy McClennan was a guitar player, and Sonny Boy Williamson was a harmonica player. And at the time I didn’t know that I would ever play myself.

We had a record player and lights in our house. We had a Philco radio that played 78s – ten of them – back around 1938, ’39. And all of the people that was out there back then was playin’ blues. I liked John Lee Williamson, which was Sonny Boy I, Jazz Gillum, Big Bill Broonzy, Memphis Slim, Lil Green, Walter Davis. Tommy McClennan was my favorite, because I idolized him. Still do – I still like him. He was so soulful, if you listen to his old stuff. That was my first real influence, other than John Lee Williamson. Them two was like running along together with me. Tommy McClennan was a guitar player, and Sonny Boy Williamson was a harmonica player. And at the time I didn’t know that I would ever play myself.

Right: John Lee Williamson, aka Sonny Boy Williamson I

Did you see many blues performers while you were living in Mississippi?

Lots of ’em, but they was all local. The only two blues artists that I recognized, one of them was Tony Hollins. I met him in Dublin, which was about 12 miles from Clarksdale. That was before I went out on my own. The next one, after I got to Clarksdale, was Honeyboy Edwards. I don’t think he was makin’ records then, but he used to travel from Chicago all the way down to the Gulf, working his way down, just freelancin’, playin’ parties and street corners and in little cafés. That’s how I seen him. Pinetop Perkins – I knew him in Mississippi, and I got to know him later here [in Detroit]. But we ran around some in Clarksdale. His name is Joe Willie Perkins. He got that name “Pinetop” from Pinetop Smith, with that “Pinetop Boogie Woogie.” And he played it note-for-note. We used to be walkin’ around in Clarksdale before I left there, and we’d go by a jukebox at a café, and a tune would be playin’. When we get where a piano was, he’d say, “Eddie, this is the way that tune went.” And he picked that stuff up just like that [snaps fingers]. That’s how good he was.

Did you ever play piano?

No. That’s my main instrument, though. I like piano. But I think I really could play if I put my mind to it.

Was your first instrument a harmonica or one-string?

Harmonica. That’s what I was blowin’. You could get one for about 25 cents back then, and I started blowing harmonicas. My first influence was John Lee Williamson, and I started blowing that kind of music. Well, the first thing I started playing was a piece of broom wire – you know, they used to be brooms out with the wire on it – and I used to tack that up on the wall. I’d use a couple of bottles, like a Coke bottle or medicine bottle [as bridges], and that’s how you tune it. You put one up near the top and another one down near the bottom, and you get your sound. I played it with a little medicine bottle in my [fretting] hand, and then I’d pick it. I was singing Tommy McClennan, just about everything that was out – boogie woogies and stuff. I was good with that wire.

In some communities, people frowned on blues music. Did you run into that in Mississippi?

No, but my dad did. See, my dad was a deacon in the Baptist church, and he played piano, guitar – like the Charley Patton-type thing. He played all that stuff. He also blew harmonica and sung. He would play for a few of the country dances at his house.

While living in Mississippi, were you aware of racism?

Yes, I was, because I grew up playing with white kids. I used to also cut their lawns, because the people I was working for, they was the boss. They had money. We was almost in their yard – just a road separated our houses. The boss was real nice, and the white kids was beautiful kids. We played football, horseback ridin’, went all down in the woods. They liked me, and at one time I thought it was the same thing – you white, and just the colors is different. But then I found out that the trend was the white folks would like you like they would their pets, like Fido. You had to go to the back door back then, even with me being a kid. They used to give me their dad’s whiskey. I was young, but I liked to drink some. I didn’t pay no attention at first, but I noticed they would pour it in this top, you know, so my mouth wouldn’t touch the bottle, and they would pour it in my mouth that way. After I really found out what that was like, it started growing inside of me. That’s one of the reasons I left Mississippi so young, because I knew that I had to get out. And I only been back there a couple of times, and now I don’t have no relatives there at all.

Were you aware of violence aimed at black people in Mississippi?

Well, black people was violent to themselves – that’s what I noticed. They would kill each other just like that [snaps fingers]. There’s so many people got killed in Mississippi, and I know that for a fact, because I’ve went to some funerals. People wouldn’t go nowhere, and the guy that did the killing might wind up at the funeral of the other person! So long as you wasn’t killin’ no white folks, you was all right.

Did you run into Rice Miller, Sonny Boy Williamson II, when you were young?

Yes. I was born in ’28, so this must have been somewhere around 1935. We were living on a plantation there, my mother and them was, out on old 49 Highway. It was a blacktop road, two lanes. The old Greyhounds – looked like school buses back then – used to come right by our house, ’cause we stayed out there on the road. And one day I was walking with another man, and we met this tall man coming down the road with these cut-up shoes on and this belt around his waist and all of these harmonicas in these holsters. This man stopped Sonny Boy, which was Rice Miller, and wanted to know would he play him a song. This man gave him one little thin dime, and Sonny Boy stopped right there and he played a song called “Good Whiskey” by Peetie Wheatstraw.

belt around his waist and all of these harmonicas in these holsters. This man stopped Sonny Boy, which was Rice Miller, and wanted to know would he play him a song. This man gave him one little thin dime, and Sonny Boy stopped right there and he played a song called “Good Whiskey” by Peetie Wheatstraw.

After that I heard him on this King Biscuit Time program in Helena, Arkansas, and once he played at the school where I was goin’. All of the kids and their parents were there at the school to see Sonny Boy and his bunch that he had there in Helena on the radio. They had a drawing for some King Biscuit, and that was interesting to the people because that King Biscuit flour, man – oh, it were sellin’. The biscuit would really rise up. So Sonny Boy played some guitar that night. He wasn’t a good guitar player, but he did mess around with the guitar. I believe his guitar player was Joe Willie Wilkins. Dudlow was on piano, Peck was on the drums, and Sonny Boy was on harmonica and vocal. So that was the second time that I had seen him.

Then after I left my parents and everybody and went to Clarksdale, I was my own man then. Sonny Boy used to play at a spot in Clarksdale, up in the upper brickyard, called the Green Spot. What I remember then about him, mostly, other than bein’ on the radio, was one Sunday night they was playin’ there at the Green Spot, and they had a crap house – where they shoot craps – in the back. By then, I must have been about 16, and Sonny Boy called “show time.” The guys was still in the crap h ouse. He was real temperamental, and he got mad and came in and got his harmonicas out. When the band got ready to come up, he was already playin’. So he told them he’d see them tomorrow back on the radio. [Laughs.] “I’m gonna play this by myself.” And he played it by himself! He played Eddie Vinson’s “Kidney Stew,” Joe Liggett’s “Honeydripper” and “Tanya,” and “I Love You for Sentimental Reasons” by Nat King Cole. And when he got through playing, all the people went crazy, and I did too, because I was used to listening to Sonny Boy I [with a combo], and I didn’t realize all of this music was in this one little instrument. And he was blowin’ this stuff just like it went, just like it was made. I really got hot on the harmonica after that. Whenever the big boys – like 18, 19, 20 years old – would spring a key [break a key inside the harmonica] they would give me the harmonica. Now it sounds like it’s bending, but it’s really sprung. [Laughs.] So that’s how I really got off into the harmonica, and I wound up learning how to blow like that.

ouse. He was real temperamental, and he got mad and came in and got his harmonicas out. When the band got ready to come up, he was already playin’. So he told them he’d see them tomorrow back on the radio. [Laughs.] “I’m gonna play this by myself.” And he played it by himself! He played Eddie Vinson’s “Kidney Stew,” Joe Liggett’s “Honeydripper” and “Tanya,” and “I Love You for Sentimental Reasons” by Nat King Cole. And when he got through playing, all the people went crazy, and I did too, because I was used to listening to Sonny Boy I [with a combo], and I didn’t realize all of this music was in this one little instrument. And he was blowin’ this stuff just like it went, just like it was made. I really got hot on the harmonica after that. Whenever the big boys – like 18, 19, 20 years old – would spring a key [break a key inside the harmonica] they would give me the harmonica. Now it sounds like it’s bending, but it’s really sprung. [Laughs.] So that’s how I really got off into the harmonica, and I wound up learning how to blow like that.

Was there a favorite brand of harmonica back then?

It was a harp was being made in Germany – might have been Hohner. It was a heavy type of harmonica. It ain’t made like that today. And that harmonica had a real nice loud tone to it, nice mouthpiece. It was kind of thick, like the way it was made back then, and it had screws on the sides. That’s what I remember.

Were players doing anything special to make them sound good, such as dipping them in water?

Ah, yes. I used to do that. I didn’t never see Sonny Boy do it. It made the keys super. Yeah, they sound different. But the only thing was you had to keep doin’ that to the harmonica, because your keys then would start stickin’. You had those little wooden teeth in there, you know, and they would swell if you put lots of water in it. But yes, when I came here [to Detroit], I was blowin’ the harmonicas. You heard this “Burnin’ Hell” and all them tunes with me blowin’ with Hooker? That’s what was happenin’. We cut that stuff in 1948, and I was blowing a harp called American Ace, a little cheap harmonica that I bought for about $1.25. That’s the kind I was buyin’, and that’s what I would blow. I didn’t have but one.

What key would you buy if you only had one?

C. It was a C then. American Ace probably come in more than one key, but I was blowin’ a C because it was tight.

So the guitarists would be playing in G?

Yes. The first guitar player I had – he and I came here to Detroit together – was John T. Smith. At that time, he didn’t have a clamp [capo], so he would use a pencil with string around the neck. It was considered as a clamp. And that’s how you would change [keys]. So he played in the key of G, the key of E – I think he didn’t play no more than in about two keys. But anyway, he would use this pencil. The first place I saw someone do that was in Mississippi at the house parties, what we called “house breakdowns.”

Why did you leave Mississippi?

I left Mississippi to work for the Illinois Central because this labor agency came down there. They would travel into towns like Clarksdale because they needed workers up in the North. Your ride was free, and you had a job waitin’ on you. I was on the emergency gang in Iowa, a troubleshooter. It was a good job. John T. Smith had got out of Chattanooga, Tennessee, the same way. He had left the railroad and I had left the railroad, and we both came to Waterloo, Iowa. So we met because he was a guitar player and I was a harmonica player. We were playing on the street corners, and we made a good team and started playin’.

How did you wind up coming to Detroit?

There was a lady that lived here; we called her Big Mary. She came over that summer to Waterloo on a vacation, and we met her. Next thing I knew, her and John was goin’ together, and they was really gettin’ into it! [Laughs.] She wanted to bring him back with her to Detroit, and they wanted to bring me. This lady said she would look out for us – food, place to stay. And she did. I guess it was a big gamble, but we did it. We didn’t have nothin’.

Soon after you arrived in Detroit, you and Smith cut a single as the Swing Brothers.

Right. That came about through John Lee [Hooker]. That’s when John came in the picture. We was playin’ at a house party, because house parties was good when we got in town. Couldn’t play in no bars – wasn’t no bars that you play no blues in. We was playin’ at this house party that Saturday night on Monroe Street. We didn’t know John Lee, but he lived right in the back of the place where we was playin’. John at that time was a partygoer – that’s what I remember about him. He was drinkin’ heavy and stuff like that. He was on his way home before day, and he heard this music upstairs. It wasn’t electric music – it was all acoustic, you know. We didn’t have mikes back then. All of a sudden there was a knock on the door, and when the landlady answered, it was John Lee. He came in, and we met him. He told us he was John Lee Hooker, and we told him who we were.

Is this before he’d cut “Boogie Chillen”?

No, he had cut “Boogie Chillen,” but it wasn’t out. It wasn’t released. It was called “in the can” at that time. And he liked the way we sound. I was blowin’ harmonica – that’s all I did then. I didn’t learn guitar in Mississippi. I learned that here, but I learned to blow the harmonica there and got good on it in between, you know. So John listened to us that night, and then he sat in with us. That’s when he told us that he had cut this tune that wasn’t out, but he had another session comin’ up. This was a Saturday night, and he had another session Tuesday. We kept that appointment and went to the studio with him.

Was this for “Burnin’ Hell”?

Yeah. That’s when we did “Burnin’ Hell” and all them tunes. That was for Bernie Bessman. We had just met. And the same day that we did “Burnin’ Hell,” we did “Miss Eloise” and “Black Cat” and all them tunes. We did six or seven tunes of his, and John T. is taking some solos on some of that stuff. We was talkin’ about that waterin’ the harmonica? Well, there wasn’t no water, so we had about six or seven fifths of this cheap whiskey, rockgut. I got one of them bottles, poured it in my harmonica, and all the keys stuck but about two or three! [Laughs.] I’m doin’ all that blowin’ that you’re hearin’ on about three keys throughout the whole thing, but Bernie Bessman still liked it! On “Burnin’ Hell,” you hear some little squeaks in the harmonica, like something got in your throat or something. And I didn’t have another harmonica, so I had to make that one do.

Bessman. We had just met. And the same day that we did “Burnin’ Hell,” we did “Miss Eloise” and “Black Cat” and all them tunes. We did six or seven tunes of his, and John T. is taking some solos on some of that stuff. We was talkin’ about that waterin’ the harmonica? Well, there wasn’t no water, so we had about six or seven fifths of this cheap whiskey, rockgut. I got one of them bottles, poured it in my harmonica, and all the keys stuck but about two or three! [Laughs.] I’m doin’ all that blowin’ that you’re hearin’ on about three keys throughout the whole thing, but Bernie Bessman still liked it! On “Burnin’ Hell,” you hear some little squeaks in the harmonica, like something got in your throat or something. And I didn’t have another harmonica, so I had to make that one do.

I didn’t know that Bernie Bessman was gonna cut me that same day. That wasn’t in the plan. I had done wrote one tun e, “Noteriety Woman,” and I didn’t have but one tune. And Bernie, after we got through with Hooker’s session, then he said, “I want to cut you.” I said, “What?” He said, “Yeah. How many tunes you got?” I told him one. And that “Papa’s Boogie” [the flip side of the “Notoriety Woman” 78]? I made that up right there in front of the microphone.

e, “Noteriety Woman,” and I didn’t have but one tune. And Bernie, after we got through with Hooker’s session, then he said, “I want to cut you.” I said, “What?” He said, “Yeah. How many tunes you got?” I told him one. And that “Papa’s Boogie” [the flip side of the “Notoriety Woman” 78]? I made that up right there in front of the microphone.

What inspired “Notoriety Woman”?

I kind of got the idea from John Lee Williamson, because I could blow just like John Lee Williamson back then. And the way I’m singin’ it, it kind of remind you, although I didn’t have that heavy voice like him. But I could ’personate him real good. But, you know, you do have some influences when you first start out.

Did you and Hooker do much womanizing?

Yeah. Did you ever meet his wife, Maudie? That’s something else about when we met. I was new here, and I had gotten a job at a factory, workin’ for Alcoa Aluminum. I had got here in August, and now I been here about three months, and Christmas was coming up. It was starting to get cold. I was a little panicky about being here in the winter, because by that time I was on my own. We wasn’t no longer with the lady that brought us here. And that’s when Hooker told me about his mother-in-law likin’ young men. So . . . [Smiles.]

Did she let you stay with her?

Mm hmm. One of the best ladies I ever had, and I was young too. She had a lot of kids.

You learned guitar fairly quickly right around this time.

I did, yes. Well, I had a lot of good influences here [in Detroit]. I learned on the jazz guitarists, John Lee Hooker. Arthur Crudup and Tommy McClennan – those was my main two, and then T-Bone Walker when I started changin’, Johnny Moore and the Three Blazers. See, I play all of those different styles.

Help support this blog and independent music journalism by making a small donation via the Paypal button at the bottom of this page.

Did you learn chords and solos at the same time?

No. I learned chords later, from experience. I just picked the guitar up and started pickin’ it. I always was a leader – a lead guitarist – after I got away from the way the older guys used to play blues. You know, you used to accompany yourself, something like Lightnin’ Hopkins, Arthur Crudup, Tommy McClennan, guys like that. It [playing chords] was already out there. Called it “barre chording” – that’s without the clamp – and you make your own positions with your hand. And that’s when I really started changin’ my music. Because all up until that time, I was playing “open,” like E natural, keys like that.

Ever learn bottleneck?

No, no. I really don’t like bottleneck too well. Some people are real good. Robert Nighthawk was good with it. Tampa Red was good with it. Muddy Waters was okay with it. And you got a lot of people today playin’ it, and it’s all right. But a lot of people overplay, and I don’t like it when it’s like that. See, by me playing that straight piece of wire [his childhood one-string], it kind of reminds me of that.

Many of your records through the years have had a similar guitar tone. You’ve stayed true to the way you hear the instrument.

Yes. It’s just like a kid growing up: You have to grow into this. See, I been a musician now for 52 years. You gotta have an open mind and ear. I play by sounds. I don’t play by what I see somebody do; I play by what I hear. And my memory is real good. It’s sharp, and I can remember just about everything I hear that’s got me on it. You know, you can’t play no notes that hasn’t anybody played. It’s the way you put it together. That’s why I don’t really go out for this copycat thing, because you can’t beat the person that invented it.

When is the first time you saw an electric guitar?

First, it was those DeArmond pickups that you put in an acoustic guitar. Honeyboy Edwards was playin’ one, and there used to be a guy down there [in Mississippi] called L ee Kizart – Joe Kizart’s brother. He had the little pickup in his guitar back then. All them guys mostly had pickups in their guitar. That’s how it was. John Lee got into that later.

ee Kizart – Joe Kizart’s brother. He had the little pickup in his guitar back then. All them guys mostly had pickups in their guitar. That’s how it was. John Lee got into that later.

Lots of ’em, but they was all local. The only two blues artists that I recognized, one of them was Tony Hollins. I met him in Dublin, which was about 12 miles from Clarksdale. That was before I went out on my own. The next one, after I got to Clarksdale, was Honeyboy Edwards. I don’t think he was makin’ records then, but he used to travel from Chicago all the way down to the Gulf, working his way down, just freelancin’, playin’ parties and street corners and in little cafés. That’s how I seen him. Pinetop Perkins – I knew him in Mississippi, and I got to know him later here [in Detroit]. But we ran around some in Clarksdale. His name is Joe Willie Perkins. He got that name “Pinetop” from Pinetop Smith, with that “Pinetop Boogie Woogie.” And he played it note-for-note. We used to be walkin’ around in Clarksdale before I left there, and we’d go by a jukebox at a café, and a tune would be playin’. When we get where a piano was, he’d say, “Eddie, this is the way that tune went.” And he picked that stuff up just like that [snaps fingers]. That’s how good he was.

Did you ever play piano?

No. That’s my main instrument, though. I like piano. But I think I really could play if I put my mind to it.

Was your first instrument a harmonica or one-string?

Harmonica. That’s what I was blowin’. You could get one for about 25 cents back then, and I started blowing harmonicas. My first influence was John Lee Williamson, and I started blowing that kind of music. Well, the first thing I started playing was a piece of broom wire – you know, they used to be brooms out with the wire on it – and I used to tack that up on the wall. I’d use a couple of bottles, like a Coke bottle or medicine bottle [as bridges], and that’s how you tune it. You put one up near the top and another one down near the bottom, and you get your sound. I played it with a little medicine bottle in my [fretting] hand, and then I’d pick it. I was singing Tommy McClennan, just about everything that was out – boogie woogies and stuff. I was good with that wire.

In some communities, people frowned on blues music. Did you run into that in Mississippi?

No, but my dad did. See, my dad was a deacon in the Baptist church, and he played piano, guitar – like the Charley Patton-type thing. He played all that stuff. He also blew harmonica and sung. He would play for a few of the country dances at his house.

While living in Mississippi, were you aware of racism?

Yes, I was, because I grew up playing with white kids. I used to also cut their lawns, because the people I was working for, they was the boss. They had money. We was almost in their yard – just a road separated our houses. The boss was real nice, and the white kids was beautiful kids. We played football, horseback ridin’, went all down in the woods. They liked me, and at one time I thought it was the same thing – you white, and just the colors is different. But then I found out that the trend was the white folks would like you like they would their pets, like Fido. You had to go to the back door back then, even with me being a kid. They used to give me their dad’s whiskey. I was young, but I liked to drink some. I didn’t pay no attention at first, but I noticed they would pour it in this top, you know, so my mouth wouldn’t touch the bottle, and they would pour it in my mouth that way. After I really found out what that was like, it started growing inside of me. That’s one of the reasons I left Mississippi so young, because I knew that I had to get out. And I only been back there a couple of times, and now I don’t have no relatives there at all.

Were you aware of violence aimed at black people in Mississippi?

Well, black people was violent to themselves – that’s what I noticed. They would kill each other just like that [snaps fingers]. There’s so many people got killed in Mississippi, and I know that for a fact, because I’ve went to some funerals. People wouldn’t go nowhere, and the guy that did the killing might wind up at the funeral of the other person! So long as you wasn’t killin’ no white folks, you was all right.

Did you run into Rice Miller, Sonny Boy Williamson II, when you were young?

Yes. I was born in ’28, so this must have been somewhere around 1935. We were living on a plantation there, my mother and them was, out on old 49 Highway. It was a blacktop road, two lanes. The old Greyhounds – looked like school buses back then – used to come right by our house, ’cause we stayed out there on the road. And one day I was walking with another man, and we met this tall man coming down the road with these cut-up shoes on and this

belt around his waist and all of these harmonicas in these holsters. This man stopped Sonny Boy, which was Rice Miller, and wanted to know would he play him a song. This man gave him one little thin dime, and Sonny Boy stopped right there and he played a song called “Good Whiskey” by Peetie Wheatstraw.

belt around his waist and all of these harmonicas in these holsters. This man stopped Sonny Boy, which was Rice Miller, and wanted to know would he play him a song. This man gave him one little thin dime, and Sonny Boy stopped right there and he played a song called “Good Whiskey” by Peetie Wheatstraw.After that I heard him on this King Biscuit Time program in Helena, Arkansas, and once he played at the school where I was goin’. All of the kids and their parents were there at the school to see Sonny Boy and his bunch that he had there in Helena on the radio. They had a drawing for some King Biscuit, and that was interesting to the people because that King Biscuit flour, man – oh, it were sellin’. The biscuit would really rise up. So Sonny Boy played some guitar that night. He wasn’t a good guitar player, but he did mess around with the guitar. I believe his guitar player was Joe Willie Wilkins. Dudlow was on piano, Peck was on the drums, and Sonny Boy was on harmonica and vocal. So that was the second time that I had seen him.

Then after I left my parents and everybody and went to Clarksdale, I was my own man then. Sonny Boy used to play at a spot in Clarksdale, up in the upper brickyard, called the Green Spot. What I remember then about him, mostly, other than bein’ on the radio, was one Sunday night they was playin’ there at the Green Spot, and they had a crap house – where they shoot craps – in the back. By then, I must have been about 16, and Sonny Boy called “show time.” The guys was still in the crap h

ouse. He was real temperamental, and he got mad and came in and got his harmonicas out. When the band got ready to come up, he was already playin’. So he told them he’d see them tomorrow back on the radio. [Laughs.] “I’m gonna play this by myself.” And he played it by himself! He played Eddie Vinson’s “Kidney Stew,” Joe Liggett’s “Honeydripper” and “Tanya,” and “I Love You for Sentimental Reasons” by Nat King Cole. And when he got through playing, all the people went crazy, and I did too, because I was used to listening to Sonny Boy I [with a combo], and I didn’t realize all of this music was in this one little instrument. And he was blowin’ this stuff just like it went, just like it was made. I really got hot on the harmonica after that. Whenever the big boys – like 18, 19, 20 years old – would spring a key [break a key inside the harmonica] they would give me the harmonica. Now it sounds like it’s bending, but it’s really sprung. [Laughs.] So that’s how I really got off into the harmonica, and I wound up learning how to blow like that.

ouse. He was real temperamental, and he got mad and came in and got his harmonicas out. When the band got ready to come up, he was already playin’. So he told them he’d see them tomorrow back on the radio. [Laughs.] “I’m gonna play this by myself.” And he played it by himself! He played Eddie Vinson’s “Kidney Stew,” Joe Liggett’s “Honeydripper” and “Tanya,” and “I Love You for Sentimental Reasons” by Nat King Cole. And when he got through playing, all the people went crazy, and I did too, because I was used to listening to Sonny Boy I [with a combo], and I didn’t realize all of this music was in this one little instrument. And he was blowin’ this stuff just like it went, just like it was made. I really got hot on the harmonica after that. Whenever the big boys – like 18, 19, 20 years old – would spring a key [break a key inside the harmonica] they would give me the harmonica. Now it sounds like it’s bending, but it’s really sprung. [Laughs.] So that’s how I really got off into the harmonica, and I wound up learning how to blow like that.Was there a favorite brand of harmonica back then?

It was a harp was being made in Germany – might have been Hohner. It was a heavy type of harmonica. It ain’t made like that today. And that harmonica had a real nice loud tone to it, nice mouthpiece. It was kind of thick, like the way it was made back then, and it had screws on the sides. That’s what I remember.

Were players doing anything special to make them sound good, such as dipping them in water?

Ah, yes. I used to do that. I didn’t never see Sonny Boy do it. It made the keys super. Yeah, they sound different. But the only thing was you had to keep doin’ that to the harmonica, because your keys then would start stickin’. You had those little wooden teeth in there, you know, and they would swell if you put lots of water in it. But yes, when I came here [to Detroit], I was blowin’ the harmonicas. You heard this “Burnin’ Hell” and all them tunes with me blowin’ with Hooker? That’s what was happenin’. We cut that stuff in 1948, and I was blowing a harp called American Ace, a little cheap harmonica that I bought for about $1.25. That’s the kind I was buyin’, and that’s what I would blow. I didn’t have but one.

What key would you buy if you only had one?

C. It was a C then. American Ace probably come in more than one key, but I was blowin’ a C because it was tight.

So the guitarists would be playing in G?

Yes. The first guitar player I had – he and I came here to Detroit together – was John T. Smith. At that time, he didn’t have a clamp [capo], so he would use a pencil with string around the neck. It was considered as a clamp. And that’s how you would change [keys]. So he played in the key of G, the key of E – I think he didn’t play no more than in about two keys. But anyway, he would use this pencil. The first place I saw someone do that was in Mississippi at the house parties, what we called “house breakdowns.”

Why did you leave Mississippi?

I left Mississippi to work for the Illinois Central because this labor agency came down there. They would travel into towns like Clarksdale because they needed workers up in the North. Your ride was free, and you had a job waitin’ on you. I was on the emergency gang in Iowa, a troubleshooter. It was a good job. John T. Smith had got out of Chattanooga, Tennessee, the same way. He had left the railroad and I had left the railroad, and we both came to Waterloo, Iowa. So we met because he was a guitar player and I was a harmonica player. We were playing on the street corners, and we made a good team and started playin’.

How did you wind up coming to Detroit?

There was a lady that lived here; we called her Big Mary. She came over that summer to Waterloo on a vacation, and we met her. Next thing I knew, her and John was goin’ together, and they was really gettin’ into it! [Laughs.] She wanted to bring him back with her to Detroit, and they wanted to bring me. This lady said she would look out for us – food, place to stay. And she did. I guess it was a big gamble, but we did it. We didn’t have nothin’.

Soon after you arrived in Detroit, you and Smith cut a single as the Swing Brothers.

Right. That came about through John Lee [Hooker]. That’s when John came in the picture. We was playin’ at a house party, because house parties was good when we got in town. Couldn’t play in no bars – wasn’t no bars that you play no blues in. We was playin’ at this house party that Saturday night on Monroe Street. We didn’t know John Lee, but he lived right in the back of the place where we was playin’. John at that time was a partygoer – that’s what I remember about him. He was drinkin’ heavy and stuff like that. He was on his way home before day, and he heard this music upstairs. It wasn’t electric music – it was all acoustic, you know. We didn’t have mikes back then. All of a sudden there was a knock on the door, and when the landlady answered, it was John Lee. He came in, and we met him. He told us he was John Lee Hooker, and we told him who we were.

Is this before he’d cut “Boogie Chillen”?

No, he had cut “Boogie Chillen,” but it wasn’t out. It wasn’t released. It was called “in the can” at that time. And he liked the way we sound. I was blowin’ harmonica – that’s all I did then. I didn’t learn guitar in Mississippi. I learned that here, but I learned to blow the harmonica there and got good on it in between, you know. So John listened to us that night, and then he sat in with us. That’s when he told us that he had cut this tune that wasn’t out, but he had another session comin’ up. This was a Saturday night, and he had another session Tuesday. We kept that appointment and went to the studio with him.

Was this for “Burnin’ Hell”?

Yeah. That’s when we did “Burnin’ Hell” and all them tunes. That was for Bernie

Bessman. We had just met. And the same day that we did “Burnin’ Hell,” we did “Miss Eloise” and “Black Cat” and all them tunes. We did six or seven tunes of his, and John T. is taking some solos on some of that stuff. We was talkin’ about that waterin’ the harmonica? Well, there wasn’t no water, so we had about six or seven fifths of this cheap whiskey, rockgut. I got one of them bottles, poured it in my harmonica, and all the keys stuck but about two or three! [Laughs.] I’m doin’ all that blowin’ that you’re hearin’ on about three keys throughout the whole thing, but Bernie Bessman still liked it! On “Burnin’ Hell,” you hear some little squeaks in the harmonica, like something got in your throat or something. And I didn’t have another harmonica, so I had to make that one do.

Bessman. We had just met. And the same day that we did “Burnin’ Hell,” we did “Miss Eloise” and “Black Cat” and all them tunes. We did six or seven tunes of his, and John T. is taking some solos on some of that stuff. We was talkin’ about that waterin’ the harmonica? Well, there wasn’t no water, so we had about six or seven fifths of this cheap whiskey, rockgut. I got one of them bottles, poured it in my harmonica, and all the keys stuck but about two or three! [Laughs.] I’m doin’ all that blowin’ that you’re hearin’ on about three keys throughout the whole thing, but Bernie Bessman still liked it! On “Burnin’ Hell,” you hear some little squeaks in the harmonica, like something got in your throat or something. And I didn’t have another harmonica, so I had to make that one do.I didn’t know that Bernie Bessman was gonna cut me that same day. That wasn’t in the plan. I had done wrote one tun

e, “Noteriety Woman,” and I didn’t have but one tune. And Bernie, after we got through with Hooker’s session, then he said, “I want to cut you.” I said, “What?” He said, “Yeah. How many tunes you got?” I told him one. And that “Papa’s Boogie” [the flip side of the “Notoriety Woman” 78]? I made that up right there in front of the microphone.

e, “Noteriety Woman,” and I didn’t have but one tune. And Bernie, after we got through with Hooker’s session, then he said, “I want to cut you.” I said, “What?” He said, “Yeah. How many tunes you got?” I told him one. And that “Papa’s Boogie” [the flip side of the “Notoriety Woman” 78]? I made that up right there in front of the microphone.What inspired “Notoriety Woman”?

I kind of got the idea from John Lee Williamson, because I could blow just like John Lee Williamson back then. And the way I’m singin’ it, it kind of remind you, although I didn’t have that heavy voice like him. But I could ’personate him real good. But, you know, you do have some influences when you first start out.

Did you and Hooker do much womanizing?

Yeah. Did you ever meet his wife, Maudie? That’s something else about when we met. I was new here, and I had gotten a job at a factory, workin’ for Alcoa Aluminum. I had got here in August, and now I been here about three months, and Christmas was coming up. It was starting to get cold. I was a little panicky about being here in the winter, because by that time I was on my own. We wasn’t no longer with the lady that brought us here. And that’s when Hooker told me about his mother-in-law likin’ young men. So . . . [Smiles.]

Did she let you stay with her?

Mm hmm. One of the best ladies I ever had, and I was young too. She had a lot of kids.

You learned guitar fairly quickly right around this time.

I did, yes. Well, I had a lot of good influences here [in Detroit]. I learned on the jazz guitarists, John Lee Hooker. Arthur Crudup and Tommy McClennan – those was my main two, and then T-Bone Walker when I started changin’, Johnny Moore and the Three Blazers. See, I play all of those different styles.

Help support this blog and independent music journalism by making a small donation via the Paypal button at the bottom of this page.

Did you learn chords and solos at the same time?

No. I learned chords later, from experience. I just picked the guitar up and started pickin’ it. I always was a leader – a lead guitarist – after I got away from the way the older guys used to play blues. You know, you used to accompany yourself, something like Lightnin’ Hopkins, Arthur Crudup, Tommy McClennan, guys like that. It [playing chords] was already out there. Called it “barre chording” – that’s without the clamp – and you make your own positions with your hand. And that’s when I really started changin’ my music. Because all up until that time, I was playing “open,” like E natural, keys like that.

Ever learn bottleneck?

No, no. I really don’t like bottleneck too well. Some people are real good. Robert Nighthawk was good with it. Tampa Red was good with it. Muddy Waters was okay with it. And you got a lot of people today playin’ it, and it’s all right. But a lot of people overplay, and I don’t like it when it’s like that. See, by me playing that straight piece of wire [his childhood one-string], it kind of reminds me of that.

Many of your records through the years have had a similar guitar tone. You’ve stayed true to the way you hear the instrument.

Yes. It’s just like a kid growing up: You have to grow into this. See, I been a musician now for 52 years. You gotta have an open mind and ear. I play by sounds. I don’t play by what I see somebody do; I play by what I hear. And my memory is real good. It’s sharp, and I can remember just about everything I hear that’s got me on it. You know, you can’t play no notes that hasn’t anybody played. It’s the way you put it together. That’s why I don’t really go out for this copycat thing, because you can’t beat the person that invented it.

When is the first time you saw an electric guitar?

First, it was those DeArmond pickups that you put in an acoustic guitar. Honeyboy Edwards was playin’ one, and there used to be a guy down there [in Mississippi] called L

ee Kizart – Joe Kizart’s brother. He had the little pickup in his guitar back then. All them guys mostly had pickups in their guitar. That’s how it was. John Lee got into that later.

ee Kizart – Joe Kizart’s brother. He had the little pickup in his guitar back then. All them guys mostly had pickups in their guitar. That’s how it was. John Lee got into that later.At right: John Lee Hooker with his pickup-equipped Stella.

But once Hooker put that DeArmond soundhole pickup into his Stella, his sound was popping.

Right. Oh, yeah!

With his feet keeping time.

That was mostly John Lee. He specialized in that, and Bernie knew that. And he would take them wooden foldin’ chairs, put two of ‘em on the floor [points to under his feet], and put Hooker on top of them. And when Hooker get to playin’, you know, he get happy with it – bam, bam, bam, bam. That was it! He had his foot on a wooden foldin’ chair. That’s how he was getting that sound. And the studio we cut at still exists today. United Sounds Studio on Second. We was cuttin’ for the old man when the old man was there – Joe Syracuse.

What kind of amplifiers were you using?

Sears, Roebuck had an amp out with a double transformer. It was tube amp, big, with dials all the way across the top – Silvertone, it was called. Hooker used to have one of them. It had two big speakers – I believe it was two 12s.

What about for harmonica?

See, harmonica is something that you got to really be careful with, even today, because if you get into a place where it’s bad acoustics, you can lose your sound. You don’t hear it, and that’s dangerous for a harmonica player. So Little Walter, when he invented his style, especially when he went out on his own, he had three speakers, a P.A. Two would be out in the building, and up over his head was the other one. You got monitors to do that now, but you still can have problems because a lot of people don’t know how to set the monitors. Now, today I could blow the harmonica and don’t have to hear it – because I know the positions, I know where I’m at. And that’s the way your recording sessions used to be. You didn’t hear nothin’. When you count that music off, all the music was going into the control room. The only time you heard it again is when they play it for you.

Back in the early 1950s, some of the material you cut for JVB ended up coming out on Chess and Checker. Were you aware that would happen?

Yeah, I knew that it happened. That was Joe Von Battle. Okay, Joe was a guy that was on Hastings Street, and he was taking advantage of people. I went to him. He had a connection with Chess way back then. But that was the problem – there always was what we called a “middleman.” You might be on RCA, but RCA didn’t deal with you directly. The y didn’t know you, and that’s the way it was. And so right there was a big gap for getting cheated, because they dealin’ with the man, and you don’t know what he gettin’. You’re so glad to be there, but you don’t know what’s goin’ on. And that’s the way Joe Von Battle was. He was dealing with Chess, and I knew I wasn’t going to do nothing for him direct, such as signing contracts, but I would have signed with Chess. So I tried to give him “Treat Me Like I Treat You” to get me this connection. “Just give it to me,” you know. And after “Treat Me Like I Treat You” was a hit in 1957, he sent his contract to Chess and had Chess send it to me, and I’m supposed to be dumb enough to sign this and don’t know the difference! And I didn’t sign it. Now, Chess had done picked up “Treat Me Like I Treat You,” and it was out. And it was a hit. Chess might have been giving Joe Von Battle money, but I w

y didn’t know you, and that’s the way it was. And so right there was a big gap for getting cheated, because they dealin’ with the man, and you don’t know what he gettin’. You’re so glad to be there, but you don’t know what’s goin’ on. And that’s the way Joe Von Battle was. He was dealing with Chess, and I knew I wasn’t going to do nothing for him direct, such as signing contracts, but I would have signed with Chess. So I tried to give him “Treat Me Like I Treat You” to get me this connection. “Just give it to me,” you know. And after “Treat Me Like I Treat You” was a hit in 1957, he sent his contract to Chess and had Chess send it to me, and I’m supposed to be dumb enough to sign this and don’t know the difference! And I didn’t sign it. Now, Chess had done picked up “Treat Me Like I Treat You,” and it was out. And it was a hit. Chess might have been giving Joe Von Battle money, but I w asn’t getting any. I got $50 out of this tune – that’s all. So I got the union. I had became a Detroit Federation of Musicians member, and the representative wrote Chess a threatening letter and told them to stop playing this tune. And they did, immediately. They quit promoting it. They scared ’em.

asn’t getting any. I got $50 out of this tune – that’s all. So I got the union. I had became a Detroit Federation of Musicians member, and the representative wrote Chess a threatening letter and told them to stop playing this tune. And they did, immediately. They quit promoting it. They scared ’em.

Then after that Don Robey [of Peacock Records] wanted me, because he’d heard the tune in Texas or wherever he was. He came up here lookin’ for me. And I signed with him. But Chess and Joe Von Battle told him that if he cut me, they’d sue him. So that scared Don Robey. He’d had a suit, which he wound up losing, when Junior Parker didn’t tell him that he had a contract already with Sun Records. So Don Robey wrote me a “Dear John” and told me, no, he wasn’t gonna cut me because he was already in a suit. But in the end, he wasn’t givin’ nobody nothin’ either! He had Johnny Ace and Bobby Bland, Junior Parker, and all of them. But see, where they was really makin’ their money was out there on the road.

Which record company treated you the best?

Well, I’m gonna tell you the truth, my friend: I haven’t really had no good deals in records, as far as getting what rightfully belongs. I don’t know nobody that really gave me the propers that I rightfully should have gotten. But I still get royalties here and there. Like “Jinglin’ Baby” – I’m getting royalties from that from MCA. And they found me – I didn’t find them – after they bought Chess.

When was the prime of Detroit’s Hastings Street blues scene?

Actually, Hastings Street wasn’t really a blues scene. You had Joe Von Battle there, you had Sam Records there. There was two storefront labels on Hastings, but you didn’t have no blues club there. The only blues club that I remember that was on Hastings was Brown’s Bar, where Big Maceo used to play. And right down the street was the Three Star Bar.

You read about the Silver Grill, Jake’s Bar, the Mars Bar, Joe’s Tap Room. Do any of these ring a bell?

Yeah! All of them ring a bell, but they wasn’t no blues clubs. No. It was the swing music and Charlie Christian type thing – swing and bop music and sentimental music, which was ballads. But it wasn’t blues.

Where would you make money playing?

At first, we was playin’ around house parties – that was it. Even for Hooker. There used to be tremendous house parties. I really learned to play guitar at these house parties for a dollar and a half a night, from sunup till sundown. But Hooker went right along with us on there. He wasn’t playin’ in no clubs either. I remember his first club was the Harlem Inn. That’s the first club I played in. The Harlem Inn was on Congress Street at Mount Elliott. It was a little house [converted into a] bar that sold beer and wine. It didn’t even have a bandstand in there. Hooker was playin’ in there by himself until he got sick. See, he liked to die from somebody put a mickey in his drink. He was sick for a couple of years, but he came through that all right . And during that time, I was playin’ his music. By that time, he’d got off into the music; he really was doin’ good. His records was sellin’ real good on the jukebox, but it was a long time before he started travelin’. He looked like he had something against it, but he did get off into it later.

. And during that time, I was playin’ his music. By that time, he’d got off into the music; he really was doin’ good. His records was sellin’ real good on the jukebox, but it was a long time before he started travelin’. He looked like he had something against it, but he did get off into it later.

When he got sick, that’s how I got my first break. He told this man at the Harlem Inn that he wanted his job when he got well, and that he would keep him in musicians to replace him. He had tried two guitars, and that didn’t work. Whatever he tried, it didn’t work. So the man kept telling him, “The crowd is walkin’ out on these people that’s playing.” Hooker ran out of people to send him, so that’s when he came to me. “Ed,” he said, “why don’t you?” I said, “I can’t do that. I never played in no club before.” He said, “Yeah, but you know all of my music.” And he was right, I did know all his music, and I was playin’ it around the house parties and street corners. I went there, and I was a hit. Shortly after I got there, he got well, and then I played there some with him. And then he started travelin’, and I would take care of the Harlem Inn for him until he got back. When I formed my first group, it was at the Harlem Inn. I had a piano player, guitar, and other musicians on my sets. I always would play there until he came back, but then he was gone so much.

By me being a progressive musician, I was learning and playing everything on the jukebox. That’s the way it was, and that’s how fast I could pick the stuff up. And that was more than what Hooker was playin’. He went his own way, and he’s still playin’ that way today. That’s him! When it comes down to comparison of musicians, we’re no comparison. Even though I learned under him, started out under him and can sound like him, I don’t. I could have learned how to blow with a rack like Jimmy Reed did, but I didn’t do that even. I still blows my harmonicas on my set, but it’s just part of my show. I play so many tunes on the guitar, and so many tunes on the harmonica with the band. Little Walter also played guitar and blew harmonica like I do.

What did you think of Little Walter’s style?

I was right up on it. Still is. He was indeed what you call a modern harmonica player. Because he would listen to horns, and that’s what you be hearin’. If you listen today, you’ll notice his music is like that. His harmonica is different. When he started out, on some of his early recordings with Muddy Waters and them, he was blowin’ just like I was. I think we all got influenced from John Lee Williamson.

How did you mike the harmonica? You see photos of people with those big microphones.

Yeah. You know, they started sellin’ those. A lot of guys today, especially white boys, they buy that mike and they blow like that. That’s the way it used to be. Sonny Boy II used to use a harmonica like that. I also played with him, by the way, in the later years. He used to love Detroit, and he would come here quite often.

Let’s listen to one of your first recordings.

[We begin playing 1951’s “Making a Fool Out of Me,” featuring Burns on vocals and harmonica and John Lee Hooker on guitar.] That’s storefront. That’s what my writing was like back then. See, I didn’t never know this stuff would ever get on no record, but I was trying to get on records then. It was cut with the cutting machine – that’s how far back that goes. My wife, she laughs at that music and how I sounded back then, because I didn’t have a chance to learn about diction and stuff like that. Back then, it just came up and came out. Growing up in Mississippi, a sharecropper’s son, we didn’t know anything about no diction! You can recognize a lot of Southerners that way. Some got away from it, but maybe not all the way.

How did you get the reverb on your voice?

Well, now, they probably worked on this stuff. That stuff was cut for Joe Van Battle. Gotham Records bought this stuff from Joe Von Battle – he was selling it right under my nose, and I didn’t know this. It just came out. I also had some stuff out on Deluxe, which was King Records. I don’t know what kind of deal he was making, but either way, the money was only going back to Joe. But this is some of my first work. That’s what I sounded like back then.

Did you write this?

Yeah. I was influenced by a lot of different kind of music when I was comin’ into this stuff. Like Walter, he developed his one way, and that’s how come we could relate so good. Two things we had in common, which I didn’t know then. On a harmonica, the bass is usually on one side, but I have to turn it over, so I’m blowing bass on the opposite side, so that makes a difference. I am also left handed, but I’m blowing from the right to the left. And Little Walter did that too. That’s how I could pick up on his music, I guess, so well. See, I play guitar right-handed, like everybody else do, and when I throw, it’s right-handed, but I write left-handed. Messed up, eh? [Laughs.]

Did you use a guitar pick on your early records?

At that time I did. I don’t now.

It also sounds like you didn’t crank the amp very loud.

That was the setting in the studio, but it might have been the guitar that I’m playin’. I used to play them thick guitars. When I played on “Let’s Go Out Tonight,” I sound different because I was playin’ the same kind of guitar the jazz guitarists is playin’. I played them fat ones for years – Epiphones, Gibsons, a Gretsch. But I don’t use that now. I’m using a Tokai. On Detroit, I’m using a Gibson stereo ES-345 with the [Fender] Twin.

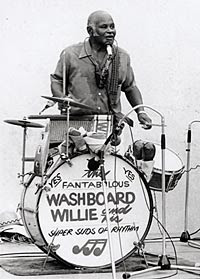

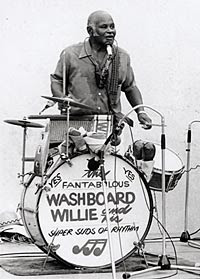

Some of those Deluxe recordings you mentioned featured Washboard Willie.

Right. Washboard Willie started out at the Harlem Inn also. He used to come there. He was funny, because he wore his apron and he had his washboard with all of these pots and stuff on it. He had a skillet too. He had that washboard around his neck and everything! He was a killer guitar player, though. ’Course, it wasn’t but one melody. I played with him a few times, but he was too tough. You play all night, you blow your brains out there, you be playin’ so much! Believe it or not, he was doin’ a lot of R&B songs back then, like Joe Turner’s “Honey Hush,” the Clovers’ “Cash Ain’t Nothing but Trash.” But you had to do all the playin’, 'cause it wasn’t nothin’ but the bass, washboard, and the drum – boom, boom – and the guitar. That was it!

wore his apron and he had his washboard with all of these pots and stuff on it. He had a skillet too. He had that washboard around his neck and everything! He was a killer guitar player, though. ’Course, it wasn’t but one melody. I played with him a few times, but he was too tough. You play all night, you blow your brains out there, you be playin’ so much! Believe it or not, he was doin’ a lot of R&B songs back then, like Joe Turner’s “Honey Hush,” the Clovers’ “Cash Ain’t Nothing but Trash.” But you had to do all the playin’, 'cause it wasn’t nothin’ but the bass, washboard, and the drum – boom, boom – and the guitar. That was it!

Do you have copies of your early singles?

Somewhat, but not on 78s, no.

When records started coming out with your name on it, did you send copies home?

Well, I used to give my mother my records. My brother and them was brought up in Chicago, and she brought all that with her to Chicago. What happened was, she loaned them to a cousin of hers, and she never did get the stuff back. But she had all of my records at one time.

Why didn’t you move to Chicago, given that it had such a happening blues scene?

I didn’t like it. I never have liked Chicago – talkin’ about livin’ there. Still don’t. You had a lot of labels around there back then, but you had some labels and things here in Detroit, because Woodward Avenue used to have lots of labels – RCA, Decca, Bernie Bessman.

Did you ever play in Detroit’s Eastern Market?

Not Eastern Market. See, I landed in Black Bottom. That was down there along Monroe Street, which used to come all the way out to around Mount Elliott Road. It was a long way from downtown. Other than the parties, I used to play in the poolrooms and on the corners.

Let’s talk about a few of the old Detroit bluesmen. Do you remember One-String Sam?

I didn’t know him personally. I was on a festival with him for John Sinclair, that Ann Arbor Blues and Jazz Festival, in ’73, I think it was. We was on that set when they featured Detroit one evening.

Bobo Jenkins.

Yeah, I knew Bobo Jenkins. I met him at the Harlem Inn. He was a photographer at that time, and he was good. He had one of those big, nice cameras where you shoot pictures and develop them. He was shootin’ ’em for money, taking them for the people in the club. He had a darkroom in a garage out back of the Harlem Inn, where he would go develop the pictures, right there on the spot. His big song was “Democrat Blues.” And the same day he cut “Democrat” was the same time I cut “Biscuit Baking Mama” and “Superstitious Blues” [released on Checker, 1954].

What was your relationship with Eddie Kirkland?

Eddie Kirkland and me started out together. At that time he was workin’ for Ford Rouge, in the foundry. And he was up on this Lightnin’ Hopkins type thing back then. We played them house parties. All of us were. Calvin Frazier was gettin’ out a little bit, and he was playin’ like T-Bone Walker. They used to call him T-Bone Walker Junior. Another guy where I got a lot of influences was Little George Jackson. He wasn’t really no blues guitarist; he’d play stuff like Charlie Christian. You never hear of him, but he was playing all of this sentimental music and swing stuff like Charlie Christian was playin’. When I first got to Detroit, if you wasn’t playin’ that kind of music, you wasn’t in it at all.

Did you ever hear of Sylvester Cotton?

I knew him. He also cut some cuts for Bernie Bessman, and then he just disappeared. I don’t know what happened to him. He played guitar, a Lightnin’ Hopkins type player.

How about Detroit Count?

Yeah. Piano player. “Hastings Street Opera.” He named everything on Hastings in that tune. [Imitates the single] “All right! I’m movin’ down Hastings Street!” Detroit Count used to play at a hotel owned by Sonny Wilson, the Mark Twain. That’s where B.B. and them used to live when they come here, because it was one of the best black hotels at that time. He played there a long time. I knew him.

used to live when they come here, because it was one of the best black hotels at that time. He played there a long time. I knew him.

At right: Bob "Detroit Count" White in 1948.

L.C. Green.

Yeah. We used to play together, and he left here and went to Pontiac. He had webbed fingers that were together, and yet he played like that!

Whatever happened to your first partner, John T. Smith?

Well, he was a woman’s man. He messed around, takin’ a guy’s wife that we knew and was kind of a friend of ours. He’d taken his wife and left and went to Cleveland. He used to work for the public works for the city. I never did see him no more after that. I don’t know what happened to him.

When Motown started becoming Detroit’s primary music, did the blues scene drop off?

Yeah. They put a hurt on blues all ’cross the country. The Memphis sound, Booker T. and the MG’s, and all that stuff was out there around the same time. James Brown, rhythm and blues type things, soul. All that music put a whippin’ on the blues. With all records, the DJs played a big part. If you didn’t have the kind of record they wanted, you didn’t get no plays, which is how your record would make it.

Was recording for Harvey Fuqua in the early 1960s a good experience?

It was. I think that’s when I really came to my best, because indeed they really was a blues label. They was R&B, like Junior Walker, Shorty Long. They had the Spinners, and Robert Lockwood cut there too, but they never did release nothin’ on him.

What inspired you to compose “Orange Driver”?

From that drink used to be out. It was some kind of orange flavor, yellow-looking, that was spiked with vodka. People was drinkin’ that stuff and getting drunk, so I figured this would be good. If you notice, I’m pretty good at things like these slang words people use. I always got an idea from that, like “I’m out of work,” “Don’t even try” – those are words that people use. I pick up all kind of stuff like that and write songs. That’s how that “Orange Driver” came about. And Harvey and them, they never did change nothin’ I’d written. They’d just clean it up with guys like Robert White, who was one of the guitar players who played on most of the sessions over there. I would rehearse with him maybe a month or two months before I cut stuff like “Orange Driver,” “Hard-Hearted Woman,” “Mean and Evil.” And they still have stuff in the can that they’ve never released on me. (Hear “Hard Hearted Woman” at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=b03TyYf5oo4.)

How did Marvin Gaye happen to play drums on “Orange Driver” and “Hard Hearted Woman”?

Because he could play drums! He wasn’t a studio drummer, but, see, I used to see him every day when we were in Studio B, which used to be on St. Antoine and Farnsworth. That was Anna Records at first. Anna was Anna Gordy, who was one of the owners. It wasn’t Motown then. I remember when Marvin was knockin’ around Anna. She was quite a bit older then he was, and they wound up getting’ married. And she was a lot responsible for his fame. See, Anna’s brother Barry Gordy was also my manager too, and I got a deal with Anna Records. When I first started recording with them, you had to be clean-shaven, mohair and silk suits and stuff. They didn’t allow us to wear moustaches. But then Harvey Fuqua and them tried to change me into a Junior Walker. I didn’t feel it then, but if I wanted to today I could go to some rhythm and blues.

What happened to Harvey Fuqua?

Harvey’s still very well alive. He’s up in New York, singin’ good. You know, he was a great pianist and he also was a great producer. So this is how I got the influence about music. After I got out there and got my feet wet, then I knew that I could do it. See, producin’ ain’t nothin’ but concentrating on hearing stuff. You don’t see it; you hear it. When a tune’s playing, I can shut out certain instruments and just concentrate on one thing, like maybe the drum or bass. That’s how I put music together: Song first, then the music. The song is always first – that’s the hardest part.

Do you have favorite keys to play in?

I like E. E is a tough key. It’s a beautiful key. It’s good for blues. Got a lot of sharps and flats in it. And you know all of them keys got at least four different positions [on the guitar fretboard] that you can play in, and each one of them is different when you learn the combinations. A lot of bluesmen don’t know that. A lot of them play on the end of the neck, but they can’t go to the middle or to different octaves.

Or they use a capo.

Which is just the easiest way of doing it. But the clamp is great if you backin’ somebody with the harmonica. It’s all right. When you playin’ the barre chord, you really don’t have that support there – you have to have the rest of the instrumentation there to play it. Yeah.

Do you have children who play music?

Yeah, I got six childrens. Four daughters and two sons. Eddie Jr. plays – he lives in Austin, Texas – and my other son, my baby boy, he fool around with the bass a little bit. All of my daughters can sing. I got grandchildren too.

If one of your grandchildren wanted to play professionally, what advice would you offer?

Go to school. Today. Blues, I feel personally, is a black tradition. A lot of people don’t agree, and anybody can play it – I’m not prejudiced about people playing it. The only difference is, when you’re playing it for me, you gotta come clean, or it gets boring. Like most of these white boys is good guitar players, but, see, blues is a feelin’, indeed, and it ain’t no lot of ’em got that feelin’! They can play the guitars – no problem – but they either overplay or they don’t put that feeling there. It ain’t about no modern times. It’s about blues. And if you get back to the old bluesmen, if them people didn’t have the blues, man, then who in the hell gonna have the blues? With all that prejudices and stuff they had – you know, fields, the boss, the woman messin’ up. The guys used to sing about it. I understand what was happenin’, because I got a little bit of that, and it made me run! Or I might have wound up the same way.

The reason I know about the blues music today and play it is because I know about the culture of it. It’s an art, just like anything else – it ain’t about no down this and that. And just anybody can’t do it. It ain’t like that. And I know a lot about what I’m doing, my friend. I actually know the blues – I know it – but it didn’t just all come from blues. It’s the whole surrounding of music. And in that music is a message. It’s there if you listen, but if you’re not listening, you won’t get to that. You’ll miss the whole boat.

I was playin’ in London, England, one time, and this particular night this young lady was in the audience. She got up and ran up to me and asked me what was I doin’ to her! See, blues music and gospel music is closely related. Some gospel singers give you the goosebumps. And it’s a funny feeling. Some people call our music, the blues music, “magic.” Some kind of black magic or evil or something, because they make this contact. And when you make this contact with it, you is gonna feel your hair crawlin’ on your arms and things. If you got some people that can perform it, that’s how they make you feel. That’s what she had. Whatever I was performin’ is the real thing. I wasn’t just playin’ for the money. If I happen to take the gig, you better believe I’m gonna do it for the people that show up. Now, that could be three people, 300, or 3,000 – it don’t make no difference. I’m gonna play for ’em, or I’m gonna leave it alone. And that’s the way I am.

What are your favorite gigs these days?

Festivals is great. The hardest thing about festivals is getting’ to ’em. You do about a 90-minute set, mostly, and that be about it. Clubs, man, is ridiculous. You got to do three, four sets. I play a few clubs here and there every now and then, but with this new breed out here, I don’t feel justified playin’ with them, because they so different. With what I know today, I have the ability to change, but I will not sell out. One time I almost came close to selling blues out, when I got off into some jazz by ear. And then I made this major discovery, which is that isn’t the way to go. With jazz, you should know how to read. And I didn’t know that I couldn’t play the blues after I had gotten away from it during the early ’60s. I had gotten off into this rhythm and blues thing, and one time I even had John Lee playin’ with me when the blues was really poor. Sonny Boy Williamson – I gave him a job during that time. But I had musicians that was playin’ everything, and I was playing with ’em. As I played this other music, I kept my music in the back of my mind, but I didn’t know that I couldn’t go back and pick that blues right up. I had to come back and get in the woodshed to get that feelin’ back. In all honesty! It got sweet. And today, you got a lot of people that straddle the fence, but they don’t know this. And they play like that so long, until if they really had to play a blues, they couldn’t do it.

You hear the expression “the blues will never die” . . .

It won’t. May not make no money, but blues music don’t ever quit sellin’. You die, but the music lives on.

Is the album called Detroit your most recent CD?